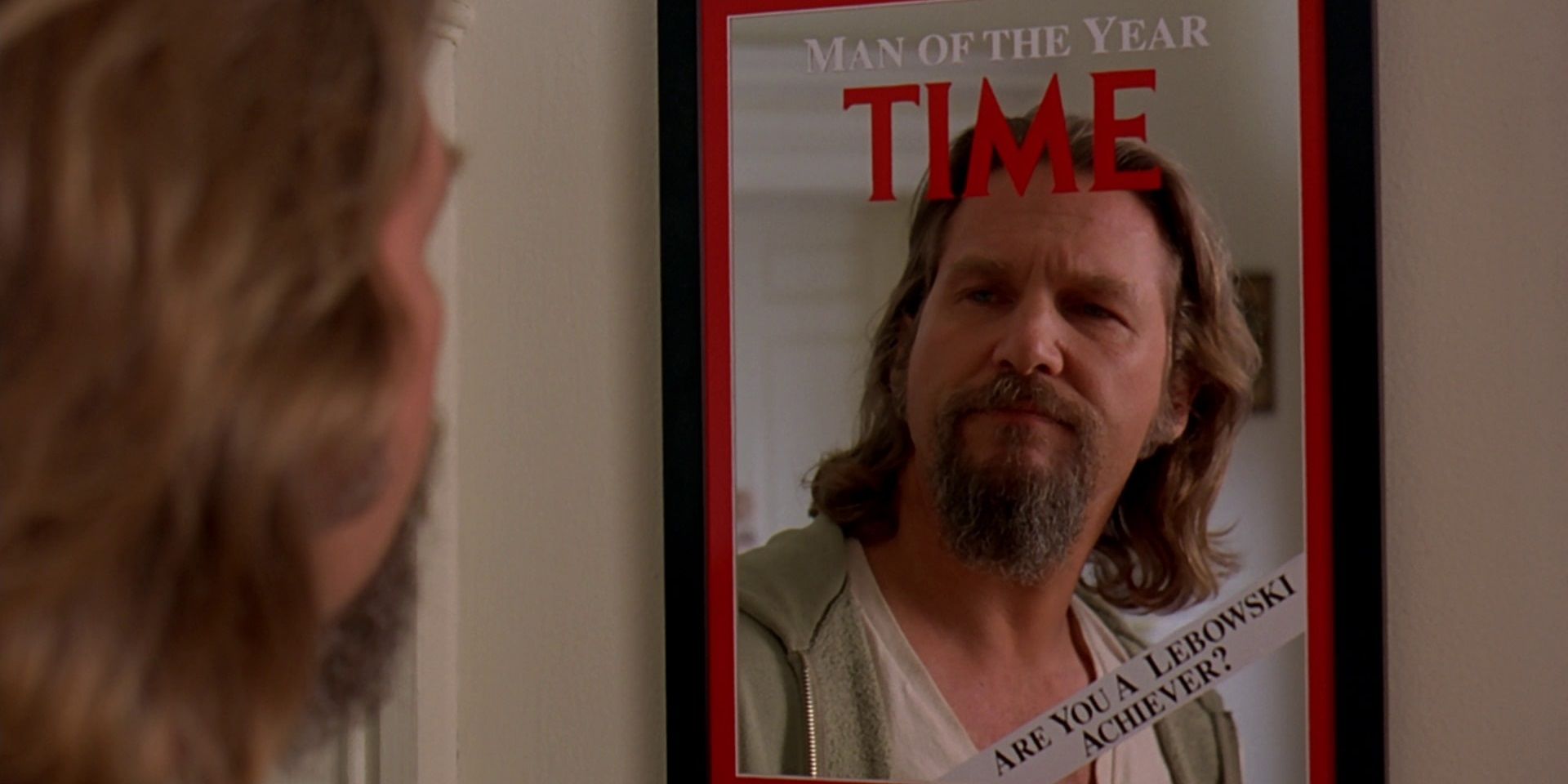

Along with Fight Club, Pink Flamingos, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show, the Coen brothers’ stoner noir The Big Lebowski is one of the cornerstones of cult cinema. Diehard fans around the world quote lines, attend festivals, and drink White Russians in honor of the Dude.But before The Big Lebowski was a beloved comedy classic with a cult following, it was a box office disappointment with mixed reviews. When the movie hit theaters in 1998, it was dismissed by critics and audiences alike.It wasn’t necessarily a box office bomb – it scraped back its production budget in North America and managed to double its gross with the help of foreign markets – but it wasn’t a blockbuster theatrical run befitting a movie with its own subreddit.

One Critic Called It “A Big Letdownski”

Today, critics praise The Big Lebowski for its quirky tone, surreal visuals, colorful characters, and unique weed-hazed vision of film noir, but contemporary reviews weren’t so kind. Dave Kehr of the Daily News titled his review “Coen Brothers’ Latest is a Big Letdownski” and called the movie “tired” and “unstrung.” He decried the “episodic” plotting, which has since become recognized as one of the movie’s laidback charms.

The Guardian’s review labeled the movie “infuriating” and described its script as “a bunch of ideas shoveled into a bag and allowed to spill out at random.” Interestingly, this review makes a point of saying The Big Lebowski “will win no prizes.” This points to the main reason why The Big Lebowski was initially rejected by critics and Coen fans: they were expecting something very different.

Following Fargo

The Coen brothers were lauded from the get-go, revolutionizing independent cinema with their 1984 debut feature Blood Simple, but it took them just over a decade to break into the mainstream. The duo’s output in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s was met with widespread acclaim, but 1996’s Fargo was their first bonafide hit. Fargo was the kind of cinematic landmark the Coens needed to truly enter the pantheon of history’s greatest filmmakers. It was universally praised by critics, grossed over $60 million on a modest $7 million budget, and won two out of seven Oscar nominations at the 69th Academy Awards: Best Actress for Frances McDormand and Best Original Screenplay for the Coens themselves.

Some critics, including Roger Ebert, declared Fargo to be one of the greatest movies of the decade. Audiences were captivated by the movie’s unique blend of small-town satire and somber detective story. Fargo is noted for its pitch-black sense of humor, but it’s primarily a drama with the poignant message that crime doesn’t pay.

Not only were expectations high for the Coens’ next movie; Fargo fanatics had a very specific idea of what they wanted that movie to be. When both critics and regular moviegoers sat down in the theater to watch the Coens’ next visually stunning neo-noir, they were expecting the kind of movie that gets nominated for seven Oscars.

They were expecting a taut suspense thriller about an everyman getting in over his head in the criminal underworld. Instead, they got a rambling stoner comedy about an avid bowler getting roped into an ultimately meaningless Chandleresque mystery plot. In its own way, The Big Lebowski is as unique and brilliant and masterfully crafted as Fargo – audiences just weren’t ready for it yet.

Tonal Shifts Are The Coens’ Bread And Butter

Audiences should never go into a movie expecting one particular thing, because they’ll inevitably be disappointed if the filmmaker had other ideas. This could end up being a problem with Spider-Man: No Way Home, because Marvel fans are expecting to see Tobey Maguire and Andrew Garfield and everybody involved in the movie insists they’re not in it. Now, if the other Spider-Men don’t show up, No Way Home will be inherently disappointing.

Going into The Big Lebowski expecting another Fargo – or even just a movie whose goal is to “win prizes” – was a mistake in itself. But on top of that, the Coens’ filmography had already set a precedent for it. They followed up their first movie Blood Simple, a grisly neo-noir about double-crossing murderers, with Raising Arizona, a goofy, lighthearted slapstick comedy about a broody couple kidnapping a baby to raise as their own. In retrospect, it makes perfect sense for the Coens to follow up the somber, dramatic storytelling of Fargo with the breezy, pot-addled antics of The Big Lebowski.

It’s not characteristic of the Coens to do two similar movies back-to-back. In fact, their entire career seems predicated on the goal of exploring radically different tones and genres. Their idiosyncratic tongue-in-cheek humor is always there, but every movie they make is completely its own beast. There are no other movies quite like Miller’s Crossing, Barton Fink, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, A Serious Man, Inside Llewyn Davis, or any of the brothers’ other untouchable gems. Even their remakes of The Ladykillers and True Grit have a style and feel of their own, totally separate from the source material.

The Same Thing Happened To Burn After Reading

The exact same thing happened about a decade later after the Coens’ next big Oscar winner, 2007’s No Country for Old Men. The subversive storytelling, Hitchcockian tension, and minimalist genre thrills of No Country for Old Men earned it four Oscars out of eight nominations.

Once again, critics and fans looked forward to the next somber, dramatic, Oscar-baiting masterpiece that the Coens would bestow upon them. And once again, they were disappointed by a par-for-the-course tonal shift. Much like The Big Lebowski, the 2008 spy farce Burn After Reading polarized critics (although its cast of George Clooney, Tilda Swinton, and Brad Pitt ensured it was still a box office success).