Brian De Palma is one of the world’s most renowned and influential filmmakers. His blood-soaked gems Carrie, Scarface, and Blow Out are ranked among the greatest films ever made in their respective genres and he was an integral component of the New Hollywood movement. New Hollywood was marked by directors like Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola revolutionizing American cinema by incorporating the experimental stylings of their favorite foreign filmmakers, like Akira Kurosawa and Jean-Luc Godard.

But De Palma took his cinematic cues from one of the most renowned and influential filmmakers from Old Hollywood: Alfred Hitchcock. Unlike many of his peers, Hitchcock was already telling dark, edgy stories with an experimental approach long before the days of New Hollywood. Nicknamed the “Master of Suspense,” Hitch is as much a cornerstone of modern cinema as Kurosawa or Godard. De Palma has often been called Hitchcock’s biggest fan. All the biggest hallmarks from Hitchcock’s filmmaking – plot twists, femme fatales, voyeurism – can be seen across De Palma’s filmography.

Almost all of De Palma’s films show the influence of Hitchcock in some capacity, but the director’s most Hitchcockian movie is 1972’s Sisters. Margot Kidder plays dual roles as separated conjoined twins: a French-Canadian model, Danielle, and a murderer, Dominique. A journalist witnesses Dominique’s latest killing from across the street, believes that Danielle is responsible, and hires a private detective to investigate. Plot-wise, Sisters has little in common with Psycho, but its style and structure come together to form the ultimate homage to Hitchcock’s 1960 thriller masterpiece.

Plundering The Hitchcockian Playbook

De Palma plunders the Hitchcockian playbook in Sisters. His most crucial use of the Hitchcockian technique is treating the camera as an omniscient, unbiased observer (also seen in David Fincher’s digital camera movements). Sisters’ opening closeup shot of conjoined fetuses in the womb immediately establishes the camera-as-omniscient-observer angle.

Split-screen effects add to the camera’s omniscient presence as it shows the audience two different perspectives of the same scene simultaneously. De Palma also uses the split-screens for some fun meta commentary on genre. As Grace is talking to detectives on one side of the screen saying, “...like some courtroom drama, while a man dies?,” Danielle and her ex-husband Emil are disposing of a corpse on the other side of the screen. These parallel timelines meet in the middle in gloriously cinematic fashion as Emil takes the body into the hallway and the cops enter the building at the same time.

The most noticeable trick that De Palma borrows from Psycho, in particular, is the ol’ protagonist switcheroo. In Psycho, Hitchcock follows the point-of-view of embezzler-on-the-run Marion Crane, then the camera scrambles to find a new focus after she’s murdered in the shower halfway through the movie. (This was an unprecedented turn at the time, especially since Janet Leigh was one of the biggest movie stars in the world.) At this point, her sister Lila takes over as the protagonist. In Sisters, De Palma tells the first half of the story from the perspective of Danielle (the Marion) before abruptly shifting the focus to Jennifer Salt’s Grace Collier (the Lila), the journalist who believes Danielle is a murderer.

Character-Driven Horror

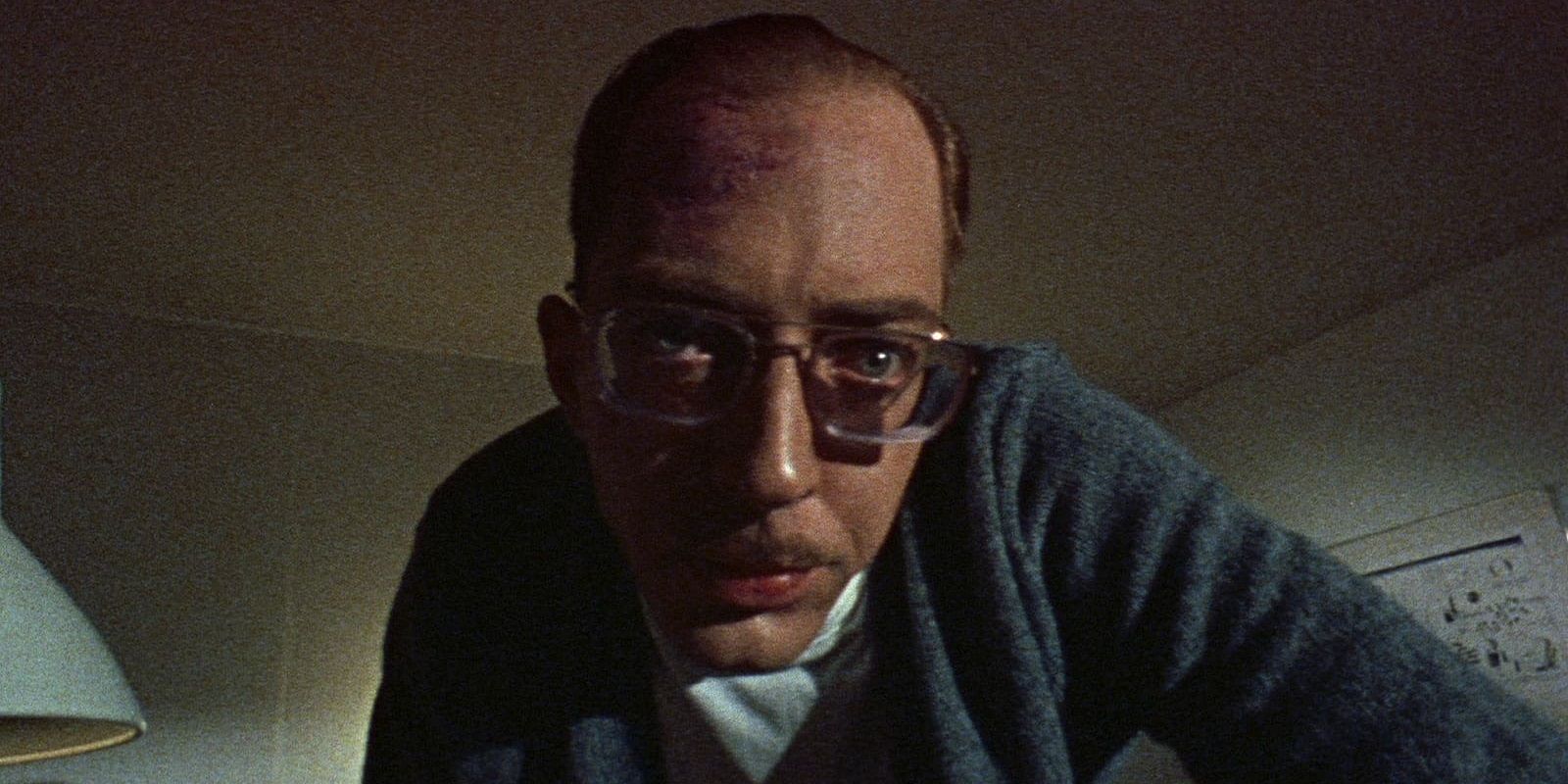

Kidder is most famous for playing Lois Lane in the Superman movies, but Sisters gave her more of a chance to show off her range. She’s incredibly captivating in dual roles as Danielle and Dominique, contrasting the innocence (and vanity) of Danielle with the cold-bloodedness of Dominique. William Finley offers a delightfully slimy and sinister counterpoint to Kidder as Emil, the toxic male villain.

Like Hitchcock, De Palma takes his time introducing the characters’ conflicts. This allows the audience to get to know them first, so that when the movie gets going and the terror kicks in, they actually care what happens to the people on-screen. In Psycho’s first act, Marion embezzles money from her boss and goes on the lam before stopping at the wrong motel. In Sisters, Danielle goes on a date that gets interrupted by her possessive ex-husband (who turns out to be cartoonishly evil). De Palma builds tension with unseen danger and unnerving music, but it’s essentially a straightforward romance for the first half-hour or so before De Palma reveals any horror elements.

In an early scene, Danielle has sex with her date, Philip, on the couch in her apartment. This scene is shockingly paid off when Danielle and Emil fold Philip’s corpse into that very same couch – all while the camera slowly pushes in on Danielle. It’s a perfect horror moment: beautifully haunting, totally disarming, and grounded in reality (we all have a couch – like a certain shower from a certain Hitchcock movie). It doesn’t rely on the jump factor to scare the audience. Once Philip’s body is tucked neatly into the sofa, Danielle and Emil casually pat the cushions back on and the camera keeps ominously pushing in.

Music By Psycho’s Bernard Herrmann

For the film’s music, De Palma recruited none other than Bernard Herrmann, a close collaborator of Hitchcock’s who composed the scores for many of his movies (including Psycho). At the time, Herrmann was semi-retired, but he enjoyed De Palma and Louisa Rose’s Sisters script so much that he agreed to work on the movie. Herrmann’s uncharacteristic synthesizers in Sisters have a surreal, otherworldly quality, like the score is from a Twilight Zone episode set on Mars, but it works beautifully. Like any great score, Herrmann’s tense Sisters music contributes at least 50% to the suspense and terror of the movie.

There’s a subtitled scene in which Danielle and Dominique can be heard arguing off-screen. De Palma slowly pans across the room and cuts away to a few extended static shots with a lot of information packed into each frame. This allows the tension to unravel while the audience is reading the dialogue on-screen. There are no visual distractions from the subtitles; the subtitles are blended into the cinematography.

One of Hitchcock’s favorite suspense-building techniques is the “bomb under the table.” If a filmmaker reveals a bomb under the table (or something that similarly indicates impending doom, like Jewish refugees hiding under the floorboards during a Nazi inspection in the iconic opening scene of Inglourious Basterds), then the audience is naturally drawn to the edge of their seats, fearful of what will follow. In Sisters, De Palma has his own bomb under the table: the knife in the kitchen. A giant knife is taken from the dishrack to cut the string around the birthday cake box. After this knife is introduced, the audience is just waiting for it to be used in a gruesome murder.

De Palma Uses Stigma To Create Tension

This is probably a script that wouldn’t get greenlit in today’s Hollywood, because its premise stigmatizes conjoined twins (Danielle’s surgery scar is revealed as the film’s first big jump scare, which is hardly positive media representation) and mental illness. But De Palma uses those stigmas to create tension. In a mental institution, Emil keeps calling Grace “Margaret” to discredit her and masquerade her as an escaped patient.

The third-act twist lands spectacularly: one minute, Grace is witnessing a murder; the next, she’s being indoctrinated into believing there was no murder by the murderer himself. This terrifying climactic hallucination is captured in a fish-eye closeup from Grace’s point-of-view with extra-grainy film – shot on 16mm by De Palma himself – punctuated by Finley’s deep, echoey, hypnotic voice. Sisters received mixed reviews upon its initial release, but it’s since been reappraised as a ‘70s horror gem. It’s a must-see for fans of Hitchcockian tension.