Everyone knows the structure. There's been a gruesome murder and a pool of suspects draws the attention of a master investigator. The detective has the skills to solve the case, and watching them do so will be the draw of the story. However, some mystery stories want to let the audience in on the clues, some want to lock them out, and some show us the answer before the investigation starts.

Murder mysteries have been enduringly popular for generations. Agatha Christie's work evolved into new locked-room whodunnits, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's grew into police procedurals, and Edgar Allan Poe's Rue Morgue inspired the entire movement. Differing views on the simple concept of solving a murder case have resulted in a spectrum of whodunnit stories.

When experiencing a murder mystery, one may feel compelled to try their hand at solving the case. A writer could choose to encourage that behavior, deliberately subvert it, or preclude it entirely. The go-to standard for mystery stories demands a writer leave breadcrumbs for their audience. It's a first-person narrative that would give the viewer every clue the detective has as they get them. These mysteries play fair with their audience, allowing armchair detectives the chance to figure it out for themselves. Some mystery stories do the opposite, providing no clues or deliberately misleading the audience with red herrings. In the worst cases, clueless mysteries end with the central detective suddenly revealing a bunch of information the audience never learned about and applauding themselves on their cleverness. Alternatively, a writer could simply depict the murder to the audience first. This leaves the audience aware of the answer, ensuring that the fun will be found in the journey, rather than the destination. The fair-play mystery, the clueless mystery, and the open mystery have strengths and weaknesses based on how they interact with the audience.

Take a show like Sherlock as an example. The 2010 BBC series starring Benedict Cumberbatch in the title role adapted several classic Sherlock Holmes stories into episode-length mysteries. However, it didn't always approach the story's relationship with the audience in the same way. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote fair-play mysteries. The reader could follow Watson's first-person narration, hear every clue as Sherlock discovers them, and come to the correct conclusion alongside the beloved detective. One could learn a lot from reading a few Sherlock Holmes stories. Unfortunately, Sherlock often excises the clues that would allow a viewer to get in on the case. It's hard to feel like part of the action when Sherlock solves every case by leaving the audience's view, learning a bunch of unrelated information, and hiding it until the moment it would be useful. This largely serves to make Sherlock look omniscient. Sherlock tries to outsmart its audience whereas the old stories made their audience smarter.

For an example of a mystery that plays fair with its audience, look no further than Rian Johnson's Knives Out. Johnson made the film to revive the classic Christie locked-room murder mystery, and he succeeded in many ways. The film gives the viewer a constant feed of information. It rarely hides anything, but the answer still isn't made obvious. For another great example, look to Edgar Wright's Hot Fuzz. Though it is a comedy and a deconstruction of American cop movies, it's also a complex mystery. The audience is encouraged to follow the clues and rewarded with a seemingly clear culprit. The audience may feel cheated when the big reveal occurs, but multiple viewings will demonstrate that even the most effectively hidden piece of the story is effectively foreshadowed.

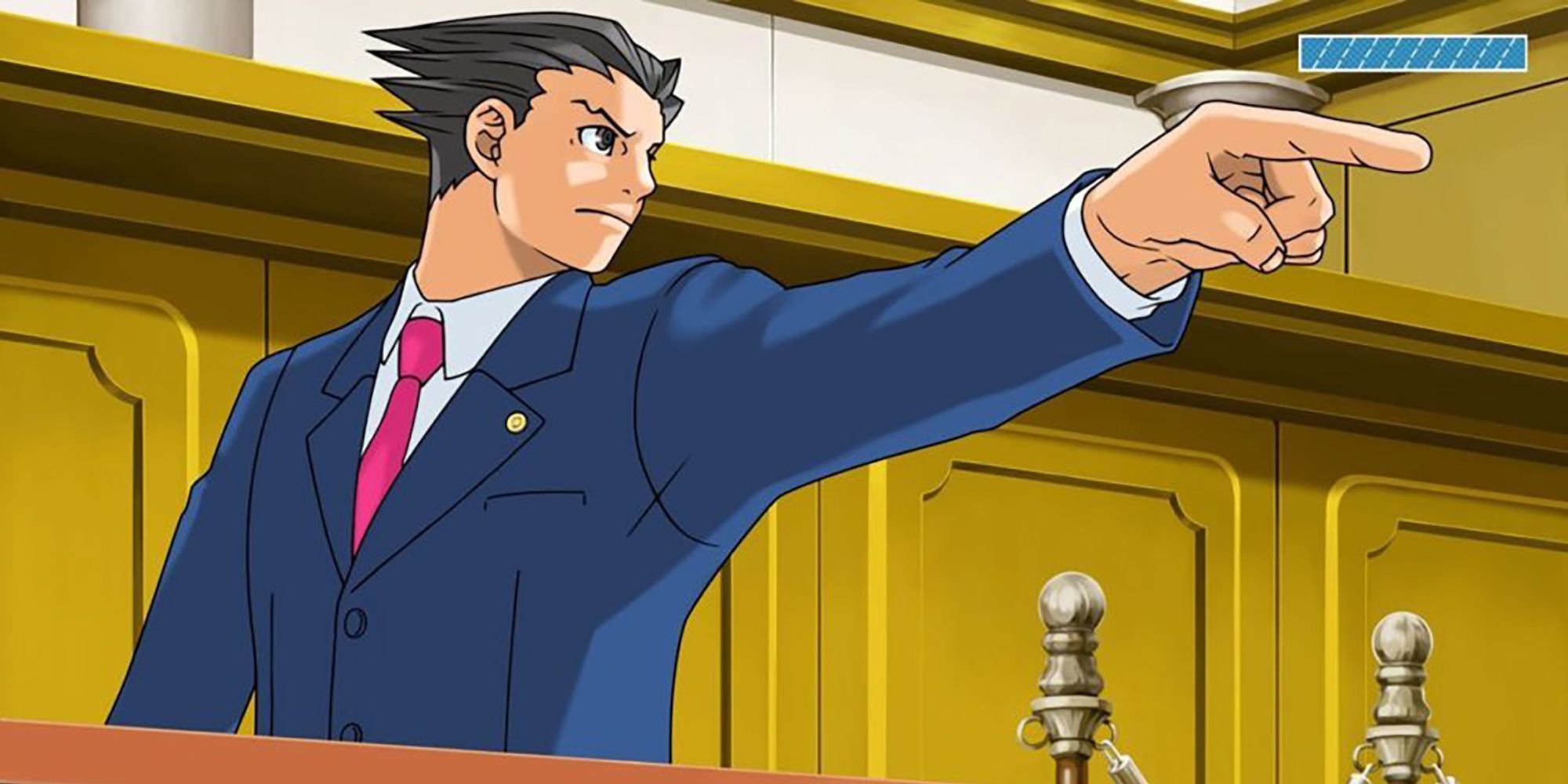

The go-to bible for open mysteries is and will always be Columbo. The long-running detective show follows a unique structure that popularized the idea of depicting the murder first. Every episode opens with the murder of the hour. Lieutenant Columbo typically locks onto the prime suspect early in each episode, then spends the rest of the runtime catching them in weak alibis and false statements. The audience knows who the killer is, but it's up to Columbo to gather the evidence necessary to send them away. The fun of Columbo is watching the eponymous detective use his facade of incompetence and folksy charm to catch the culprit in a lie and bring them to justice. This open mystery format is probably the rarest of the three, but between the show that popularized it and the Phoenix Wright franchise, it's a fascinating storytelling structure.

Mystery stories can lead the audience on a journey, surprise them with a big twist, or start with the answer and watch the process of solving it. There's no inherently wrong way to go about the process of solving a fictional murder, but there is a lot of fun to be had with the audience's expectations. As more mystery stories come to prominence, new points along this spectrum could be discovered. Who knows how the future of whodunnits could handle the genre's armchair detective fanbase?