Andrew Shouldice has dedicated the last seven years of his life to a game design passion project, and next month his hard work will be realized with the release of Tunic. An isometric adventure game with prominent Legend of Zelda influences, Tunic is a love letter to an era of gaming where instruction booklets provided additional crucial context that developers couldn't fit on the cartridge. While Shouldice's goal is to rekindle the joy of discovery that many contemporary gamers experienced early in their careers, Tunic aspires to be more than a stroll down memory lane, with mechanics and systems that challenge modern and classic conventions.

Game Rant spoke to Shouldice about the insights he has gained over the title's long development, Tunic's unique narrative philosophy, the contributions of his collaborators, and the necessary evils that are promotional spoilers. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: Can you begin by introducing yourself, and telling us what your favorite open-world adventure title is?

A: My name is Andrew Shouldice and my favorite open-world adventure game… Now I am trying to think of all the open-world adventure games I’ve played. So. Breathe of the Wild and Skyrim, I guess; both of which I enjoyed. And that’s probably it? I think the original Zelda has been cited as the first open-world game, so that has a special place in my heart, obviously.

Q: In a nutshell, how would you describe Tunic to gamers who are unfamiliar with the title?

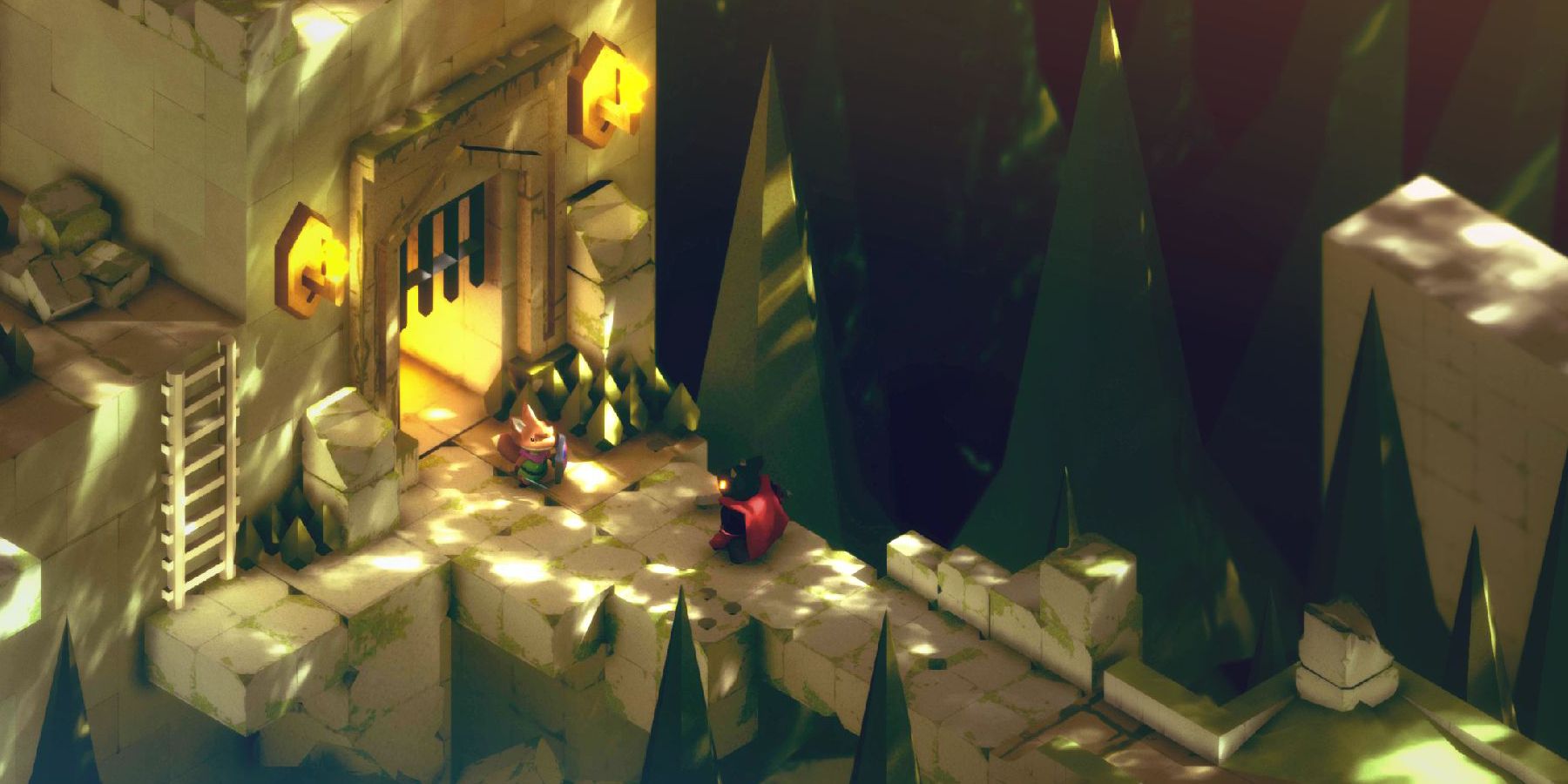

A: Tunic is an isometric action-adventure about a tiny fox in a big world where you explore the wilderness, fight monsters, and find secrets. People who’ve played it look at it often say “this looks a bit like a Zelda game.” But then they play it and see that the combat is a lot more varied and technical than say, Zelda 1. I’m sort of jumping the gun to answer commonly asked questions [laughing]. Usually, people ask what game I would liken Tunic to in the Zelda franchise. And most of the inspiration came from Zelda 1 and Zelda 2. It is a world full of mystery that is ripe for you to explore.

Q: What initially inspired you to make Tunic, and how long has the title been in development?

A: Tunic has been in development for quite some time now. I think we are coming up on 7 years, which is a while. What originally inspired it was… Well. There are a few things. But the core of it was the desire to make a game that captured the same feelings of playing a game as a kid. Say, an NES game. Playing the game, flipping through the manual, and trying to understand this cryptic world. There are lots of games out there that try to evoke nostalgia because they look, and play, and sound like classic games. But it was really that feeling of wonder and exploring the unknown that I wanted to capture.

Q: How did that relatively lengthy development cycle affect the design process? Any lessons learned, or tips for fellow indie developers?

A: Sure! I had made games before. Both in a recreational sense; making games for fun, for game jams and the like. And I also worked in the games industry, making mobile games. Mostly hidden image games. I had shipped titles before.

So, I struck out on my own to make a full-fledged commercial action game. I say struck out on my own, but you know, there is a whole team around this game now. But at the beginning it was “I can do it, and the things I can’t do I can get help with! There are going to be some trials and tribulations, it’s going to be really hard at points, but you know what? I just need to try.”

And I think the thing that I have… I don’t want to say “learned” because these are things you hear over and over again when asking for tips on striking out on your own—but the things I have come to respect more and understand more are that A) everything takes forever, and B), design is a complex, multi-faceted, multi-headed hydra of a thing. There is no right answer, in a sense. Once you know how you want this to work, you just plug away at the keyboard until it does what you want it to do. I am not diminishing the complexities of programming, but with something like design, the question is, what do you want this to do?”

So a lot of the time I spent early on, was trying to figure out what this game is. I knew the feeling I wanted to evoke. I can see the emotional payload the game was supposed to deliver, but how that crystalizes into a real-life video game. How that becomes an experience that people can play, a critical path through a world, that is something that is… It is very real. Like, “What is on the screen? What can people do? How can they interact with things?” You need to work to get to that feeling. Learning how to get to design that way was an iterative challenge.

People will often say “I could have made that game in a tiny fraction of the time,” and… well, yes. You’ve already seen the end product. And once you know that, it can be a fun challenge to implement. But really, it’s second-guessing yourself, revisiting things, and changing stuff that really will make something take a long time. So, the take-away for me, is that every game is its own little puzzle to make. You need to relearn a bunch of things as you make it. That’s what makes it a novel experience; that’s what makes it enjoyable for people to play, because they haven’t seen it before.

That’s a long answer, but really: it’s iteration. Iteration and learning things along the way.

Q: Have press and fans’ responses to the game changed throughout development?

A: I think so. First of all, in quantity. We’ve been fortunate enough to be seen by a lot of people, which is humbling and very cool. There are a lot of people who have looked at this thing and are excited about it. Which is… yeah, it’s heartwarming. But the quality of the feedback—not quality in terms of how good it is but like the nature of the feedback—has changed. At first it was “Aw, it’s so cute! I can’t wait to go on an adventure with this little fox.” More recently, people have realized it is a game of challenge and mystery. So, some of the responses are things like… well, I need to edit out the explicative, but “Gosh darn! This skeleton can go suck a lemon,” because it can be challenging at points!

But on the whole, the thing that has remained consistent in the nature of the response has been people’s enthusiasm, and their love for this little character. Which makes me smile. Like I said, people start with “Aw! It’s cute!” and then they realize it’s also this lonely, scary world full of monsters. But they all still really like the fox.

Q: The trailers and previews released so far show-off swordplay and dungeon crawling with a number of tools. What are some other core mechanics in Tunic?

A: We’ve shown a little bit of the primary features of the game, which includes the manual. It’s shown off in the trailer and there are a few sample pages in the demo. The idea is that part of the experience of playing a game from the 80s is that you might need to look through that manual to understand what’s going on.

In Zelda 1 and Zelda 2 there were hints written in the manual. I think it’s a little less of the case with Zelda 2, but in Zelda 1 there are things that you just wouldn’t find out any other way than by leafing through it and finding something written in the margin. The instruction booklet, as they were called, was sort of a fun meta-part of the game, whether you had the controller, or you were reading next to the person playing, looking at the maps for navigation, or providing hints and tips.

In Tunic, scattered throughout the world, are pages for the instruction manual of the game that you are playing, hidden within the game you are playing. And just like those old games, there are things in the manual that are probably worth your while to look at, likes maps, or a bestiary listing all the monsters. Or even what items do. And some other things which are mostly secret.

But segueing a little bit, if the player decides “Oh, I’m going to turn to the page that tells me what items do,” even there, there is some mystery. Because as people have probably seen in the trailers and the like there is this sort of strange angular runic language all over the place. These mysterious glyphs that exist not only in the UI, but in the world itself. So maybe you a signpost with glyphs next to a picture of a sword, and think “Okay, maybe the sword is in that direction,” or you may find an item next to that mysterious text, and think “I wondered what that item was about, but I need to fit some English in there to figure out what’s going on.”

That sort of thing is exciting to me. It is a product constructed for your entertainment video game player! But the hope is, the intended illusion, is that this book is keeping things from you as you go along.

Q: Do you have any personal favorite tools that players will have access to in Tunic? What are some upgrades players will encounter on their journey? In the trailer we get to see the whip and sword…

A: [Wincing] Even showing that item in the trailer was like, “ahh, I really don’t want to show this! I want it to be a surprise for people to find for the very first time,” but part of making a trailer is showing people what the video game is. As much as I would like it to be just be 60 seconds of “the game’s really cool, please buy it! Just trust me!” that won’t work. You need to spill some of the beans. So that was one of the things we showed off. And maybe it’s true nature is still mysterious. Maybe it can do some things that people don’t know yet. So, “yes” to answer your question. I do have favorites, but “no, I can’t really tell you about them.” The thing that I like is… I guess most of them fall into this category, but my favorite is not a strictly necessary thing to find.

The idea that a tool—in a Metroidvania-style game—is a key to progress is an enticing model. But more enticing, IMO, is knowing that if even if you are under-equipped, if you get lucky, or maybe just bumble your way through, you can get to an area where you are not ‘supposed’ to be. Feeling that you are transgressing, by exploring a place above your paygrade, so to speak. Being able to get in over your head… is a cool feeling. And allowing people to circumvent what we think of as the Metroidvania experience, is cool.

But to revisit the item in particular I am thinking of, it is just… a weird cool thing that maybe some people will use? Maybe a lot people won’t find it? Maybe it will change up how people play the game just a little bit? But I think it’s the sort of thing where, if you are watching a stream—or if I am on the living room floor looking over my friend’s shoulder as they’re playing it on the CRTV in 1986—it is whatever today’s equivalent to that experience is. It’s the thing where the person who sees it goes “Oh! What? Where did you get that!” and the player goes, “Huh. Where did I get that?” and then they go and show them. I think that transfer of knowledge is fun. It makes the game feel like it is… Well. Games are inherently social experiences, even if they are single-player. It would warm my heart, if that is something people ended up doing.

Q: Isometric adventure games are a rich genre with a long history. What does Tunic do with its combat to keep things fresh and interesting?

A: The main thing is that you have a combat dodge. It allows you to quickly displace yourself with I-Frames. There is a stamina bar in the game, but it doesn’t work like a traditional stamina bar. You are always permitted to do that dodge, but the main difference is that you are vulnerable, when you are at zero stamina. But there are lots of fine pointers about how it works. Maybe there is a manual page that will explain it to you! That is sort of the thing that people will notice first. Like, “Oh! There’s a stamina bar, and it goes down when I dodge, but I can still dodge and attack when it’s empty. I can still run. But I am engaging in this risk/reward as a player.” Other things include, a sort of lock-on, using left-trigger.

Orientation is important. Facing enemies is important. You can back away from an enemy while still targeting them. You will—spoiler—soon find a shield when playing the game. There is a shield hidden somewhere that you can find. But that adds a degree of technicality in that you can block incoming attacks, to an extent. That will cost stamina. And some other advanced techniques, that people may or may not find.

There are also some special techniques that you can learn from manual pages. You can bumble into them. We haven’t yet gotten into the different items you can get, but the primary way to interact with the world and enemies is your sword. But there are other tools that you can find, other weapons, that will augment that and allow you to mix things up, and deal with different encounters in different ways. The items you have mapped to your face buttons will be a matter of preference, and utility.

Q: Does Tunic feature magic or crafting systems?

A: No, not really a crafting system. Not where you take items and put them together to make a thing. There are definitely magical things in the game. And there are tools you can get that I would qualify as “magical.”

Q: How long do you estimate an average playthrough of Tunic lasts?

A: I think about that a lot, and I have never really come up with a solid answer for it. Because I wanted to say “It’s definitely 6 hours!” but I don’t think that’s accurate. For a number of reasons. One is that I always look back to some of the builds we’ve released in the past, whether they be demos, or internal testing builds, I always underestimate how long it will take people to play. So, when I think, “Well, if it takes me this long, maybe I should add 50%, or maybe I should be multiplying it by three.” So it’s hard to estimate. But that’s me wanting a super realistic number. I think if people end up spending six to eight hours on this, that seems pretty realistic.

But the other thing that makes me think that is not accurate, is that there are secrets hidden in this game—that I can’t talk about. Some of the secrets are pretty hidden. And it’s going to require people to spend a little time on it to figure out everything there is to figure out. And I don’t necessarily mean to say that “there’s a whole secret area that you haven’t found yet!” but you can realize there is a way to get to a certain spot much earlier than I ended up being here. Maybe I can find a special path, or do something tricky and… that, to me, invites people to start a new save file and see what they can get away with using those insights.

I know that obviously doesn’t contribute to the in-game time of a given playthrough, but I think the amount of time people could spend with this is much greater than six to eight hours. We have a speedrunner on the team; Kevin Regamey, who is doing the audio is also a speedrunner. And he has spent a lot of time with these builds doing unusual things with them. Actually, now we have two people doing speedruns on the team. I think there’s a lot here for people to enjoy. But if you just want to sit down and press the buttons with the fox sword character—you’re talking maybe eight hours? It’s difficult because I don’t want to over-estimate it, but I don’t also want to undersell it.

Q: Will layers eventually learn how to translate the cryptic script you mentioned?

A: Well, there’s no expectation of decoding a secret language. Who knows? Maybe it’s random, and generated at run time. However, aesthetically, I hope it contributes to that feeling of reading an instruction manual written in a language you don’t understand, or, as is the case for me, reading an instruction manual when you are still learning to read. I remember going to a Warp Zone for the first time in Super Mario Bros.. I probably knew the word “Welcome,” but that was definitely the first time I had seen either “Warp” or “Zone.” And so, it’s like, “Welcome to bizarre place unknown! Welcome to enormous mystery!” So hopefully having most of the text be these cryptic characters will contribute to that feeling.

Q: Tunic’s art style is immediately eye catching, and resembles both The Legend of Zelda and modern isometric titles like Death’s Door and Monument Valley. How did you settle on the look and feel of the game?

A: It’s an iterative process. Like I said, we’ve been working on it a long, long time. Number one, my 3D modeling skills started out pretty rudimentary. So, if I am setting out to make a big world of secrets, that world should stay pretty simple-looking. Also, I wasn’t sure how to make realistic-looking rocks, so might as well make abstract versions of them. I kept things simple for technical reasons, and the limits of my own skill. But as time went on that level of aesthetic abstraction sort of shifted around. One of my collaborators, Eric Billingsly—who was coming on fairly late in the project to work on the art style, which was by then pretty well established—recently said in an interview: “It was an interesting challenge to find that aesthetic balance. Because if you add too much detail to something, it doesn’t look like Tunic anymore. There is this conservation of visual noise, that we try to maintain. And if you have something too simple looking, it just looks like its unfinished.

It’s been a challenge to strike a balance between something that is sufficiently abstract and stylized to be visually interesting, as opposed to a hyper-realistic videogame, but also looks real. Like the blades of grass are these very angular geometric shapes and they have been since the beginning, and we try to make them move like grass. Well, they don’t even move like grass, but they do move in an aesthetically pleasing way.

As far as inspiration goes, Monument Valley was a very big one early on. That’s an isometric game that does a lot with isometry. But aesthetically, it also just has these beautiful, elegant, soft gradients. Very smooth lighting on things. A very well-considered palette. That was one of the inspirations, for sure. Use the idea of bounced lighting and bright colors to make a world look like its glowing a little bit.

Q: What can you tell us about Tunic’s story and lore?

A: This is an academic way of looking at it, but we try and make sure that the experience of the player and player character are one and the same. Your experience as a player is “I heard about this video game and it looks cool. So now I have it, and I’m going to play it.” When you start the game, you wake up on a beach as a fox with no idea what you are doing. You are here for a reason, but that reason could be to have fun, look for treasure, maybe you heard that there is something specific to be found in this area. And that is the story. You the player are interested in this videogame. Are you going to find what you are looking for? I hope so. Are you going to find more than what you were looking for? Possibly. Are you going to get yourself into trouble? Probably!

My favorite way to tell a story is to have them ‘be.’ Like, the story has already been told, and you are looking at the remains of it. Ruins are just aesthetically fascinating to me. The idea of exploring a world, and piecing together… not necessarily ‘The Story,’ but your own thoughts about what happened or could have happened in this place is what is most interesting to me. It is a story that is not an act of consumption, so much as an act of creation.

That’s why mysteries are fun! Because you are speculating about what could be. That’s sort of a b******t explanation of what the story is, but our goal is simple: you are the fox, and this is your adventure.

Q: Is there a large cast of characters in Tunic, or is it a more intimate ensemble?

A: It is a fairly lonely experience. Circling back to the beginning, much like Zelda 1, you are exploring a space, and maybe you find a silent person in a cave. The same is true of Tunic. You are a stranger in an abandoned place. I don’t want to give anything away, but exploration is the core of the experience.

Q: What is it like working with Power Up Audio and Lifeformed? How have their sounds influenced the game’s development?

A: Both Power Up (Kevin Regamey) and Lifeformed (Terence Lee and Janice Kwan) came onto the project fairly early on. I had been working on the game for maybe a year or less when I started reaching out for help with audio stuff. Because I needed help with audio stuff. I can’t write music, and the sound effects I made were pretty bad. Both Kevin’s and Terrence’s contributions have gone way beyond merely producing waveforms for the game.

Like I mentioned before, Kevin is a speedrunner and he has provided a bunch of insights. He is also accustomed to hiding secrets in audio—in fact, he made a whole game about secrets hidden in audio. If anybody is familiar with Kevin’s work, it is not a spoiler to expect some secrets hidden in his contributions to the game. In a more touchy-feely way, any time I add work from either of them into the game, it feels like it comes to life in a way that is very, very cool. I’ve looked at an animation thousands and thousands of times, but when it is accompanied by audio, it comes to life in a way that is brand new. I say this a lot, but when we do team meetings and stuff, “Wow, folks! It feels like a real video game now!” and it keeps feeling more like a real video game as everybody adds their parts.

Again, I’m trying to think of other things I could add without too many spoilers, but suffice to say, it has been really cool working with them. Of all the people on our weekly team calls, I am the person with the most limited experience in shipping games. As I mentioned, I have shipped titles before in a previous life—in a different genre—but everybody else has worked on big titles. So I feel very fortunate to have that support, not just from Finji, who provides very real publishing support day by day, but also just the idea that there are people working on this who know what they are doing.

So yes. Terrence and Power Up are both world-class, and I am very happy to be working with them.

Q: How many people are working on Tunic? Can you describe the dynamic of your team?

A: Here’s what our weekly meeting looks like: there’s me, obviously, there’s Terrence and his wife Janice from Lifeformed, there’s Kevin, and there’s Finji, most notably Adam and Rebekah Saltsman who run that studio out of Grand Rapids Michigan. They provide not only provide publishing support, but emotional support, and design consultation. There is Eric Billingsley, who came on a couple years ago when a lot of the game was complete, and a lot of the game was sort of a gray box. Together, we have tackled the entire game and made it look a lot better. He does a lot of shader work, and as a programmer, he worked on Cuphead. So, he is another multitalented person who has been doing bug fixes and shader optimization. Early on, Felix Kramer helped me on the path of getting this game in front of as many people as possible, providing business development. There are more people as well! We have a third party porting studio that is helping out, and Finji’s QA team is helping a lot, and beta testers, and emotional support. But if we are talking core creative team, it is myself, Kevin, Terrence, Eric, Adam and Bekah.

Q: What games do you play to unwind, and which titles do you look to for inspiration?

A: At this point, we are crossing our T’s and dotting our I’s, so I haven’t been playing a whole lot of video games that are directly comparable, at least at this exact moment. But to unwind, I’ve been playing a lot of Ace Attorney. My partner started me on the trilogy about a year ago, and I recently just wrapped it up and started playing Apollo Justice on a DS. And that’s been really nice, because it has basically nothing to do with an exploration/action video game and it’s been a nice sort of palate cleanser.

Q: Indie game development has been flourishing for several years now. Have you learned any lessons from watching other projects, or do you follow other creators you admire?

A: Yes, but I feel like I haven’t been keeping up. There are definitely a lot of people that I looked to when I was first getting started. There are plenty of people I find inspiring in my life, but as for who I am following on social media? I don’t have a list off the top of my head. I’ve actually been trying to stay off the internet lately.

But in terms of what I’m looking forward to, or what I have admired from afar in the indie space… Another Finji project, Chicory: A Colorful Tale, is a game that came out last year, and it is just tremendous. It looks great, it sounds great. The soundtrack is just staggering. I had the opportunity to talk to the director of the game, Greg [Lobanov]. Actually, we’ve met a couple times, as he’s done some playtesting for Tunic.

Also, as part of an event last year, we jammed on some ideas relating to what it means to be a Zelda-like game, and what you can do differently in that space. He and the Chicory team made a game that was super positive, and about moving forward, checking all your boxes, but also being okay with not being able to check all the boxes. It had a very strong message, whereas Tunic is very silent and cagey about things. That was an interesting conversation, and I believe that’s what led to him play-testing Tunic. He provided some very useful Feedback.

So yeah, if you haven’t played Chicory: A Colorful Tale, you should check it out.

Q: Do you see yourselves continuing Tunic as a series, adding post-launch content, or view the game as a self-contained entity?

A: My favorite thing in the world is to add polish, detail, and new things. Kevin will ping me on Slack and say “I just noticed you added this thing! I didn’t know this was in the game. You know we need sounds for this, right?” I can’t really make any promises. I may just want to take a break when it’s done. It was meant to be this singular artifact, and so building a second one would be strange. I don’t know what that would be like. Nothing official on that subject.

Q: With release just around the corner, what final preparations remain before launch?

A: Finishing up manual pages. There are a bunch of polish tasks, but that’s a big one. Bug fixes and optimization. Making sure all the different secrets work, and there are a bunch of them, so it’s a daunting task. Putting in SFX is another. I have a big spreadsheet of sound effects that need to go in. It’s all… well, it’s mostly very satisfying to be getting through the end of it. Sound effects especially. As I said before, they really make it feel like a video game.

Q: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about Tunic?

A: Tunic is coming out March 16th. You will be able to play it on computers and Xbox. Wishlist it on Steam, and sign up for our mailing list at TunicGame.com!

[END]

Tunic is set to release on March 16 for PC, Xbox One, and Xbox Series X/S.