There is much to be excited about in Stranger Things’ fourth season. Netflix released the new episodes mere weeks ago, but fans have since been fascinated by the marvelously creepy performance of Jamie Campbell Bower as the season’s surprise villain, One. Yet some viewers will be unsurprised by Bower’s ability to balance the menacing with the enticing. For some viewers, his performance might even seem oddly familiar…because the actor embodied those same traits in a previous role. As Anthony Hope, the doe-eyed standard-bearer for dewy heroism in Tim Burton’s 2007 adaptation of Sweeney Todd, Jamie Campbell Bower not only toed the line of ghoulish virtue — his performance encapsulated the moral fallacies that the musical subverts to turn heroes into villains (and villains into meat pies).

Long-time fans of musical theater icon Stephen Sondheim tend to know what they should expect from his musicals. Sexual innuendo and social critique run fast and thick in Sondheim’s lyrics, from the outlandish gimmicks of Gypsy’s strippers to the uncomfortable double entendre of Into the Woods’ predatory wolf. Sweeney Todd is no different; the only male character who presents as wholly unproblematic is young Toby (whose emotionally-regressive adulthood is almost assured after what the story puts him through). This moral complexity made the project a perfect fit for Tim Burton, whose filmography is paved with ethically ambiguous characters in larger-than-life scenarios.

“Boy gets girl. Boy loses girl. Boy sings a song and gets girl.” That is how Frank Sinatra, in documentary musical revue That’s Entertainment, summed up the plot of traditional Hollywood musicals (and their Broadway counterparts). It is also, more or less, how Anthony’s story progresses in Sweeney Todd: he sees Johanna from a distance and falls immediately in love with her (“Boy gets girl”), before she is shipped off to Bedlam, out of his reach (“Boy loses girl”). Except walls cannot protect Johanna from Anthony's determination to redeem her (“Boy sings a song and gets girl”). To Anthony, he is the hero, rescuing Johanna from the evil Judge Turpin. If the foundation for Anthony’s romantic quest seems a bit thin, it is supposed to be. Besides lampooning the flimsiness of traditional musical plots, it underscores his folly in believing that his life could be a musical, his love story as straightforward as a song.

In other movie musicals, the story usually invites the audience to suspend disbelief; to pretend, for a few hours, that relationships can be founded on nothing more than a brief encounter, that they are not complicated and fraught. Sweeney Todd is different: the show encourages its audience to remain skeptical, so the story can expose how rose-colored glasses tend to cloud real-life relationships. Anthony’s fixation on Johanna has little to do with her; rather, he is more invested in the dream of himself as a savior than he is in getting to know her, in helping her to improve her situation. Johanna is an idea to him, and not a person — he is “satisfied enough to dream” her. Even the childish physical description of her “yellow hair” reminds the audience that his love is a fantasy built on the flimsiest of foundations.

Meanwhile, another character in the show is pining after a distant vision of a woman with “yellow hair.” Mr. Todd is pursuing his revenge quest against Judge Turpin, ostensibly in service of the wife he presumes dead, Lucy. Yet his underlying motive is only his own satisfaction, as killing the judge will not materially help Lucy, whom Judge Turpin victimized; in case the audience might miss this nuance, the show makes it explicit by turning Todd into Lucy’s actual murderer. He is so consumed with the vision of who she was that he does not recognize her when she stands before him — his only thought is to get her living, broken person out of the way before he commits his final, cathartic murder.

As for Johanna, his living daughter, Todd uses Anthony as a tool to liberate her from the judge, but he does not seem to care as much about the object of his quest as the completion of the quest itself. The lyrics of the “Johanna” reprise connect Todd’s self-serving vision of his daughter (“I’d want you beautiful and pale / The way I dreamed / You were”) to Anthony’s dream of “stealing” Johanna, weaving the two strains into a duet that further incriminates the would-be hero. (Lucy, still alive at this point, stands on the corner adding her warning screeches to the medley — an avatar for every viewer who, having escaped a toxic relationship, tries to warn others of the red flags.) Like Mr. Todd, Anthony believes he is offering salvation; like Mr. Todd, he is only projecting onto his feminine ideal a need to validate his own righteousness.

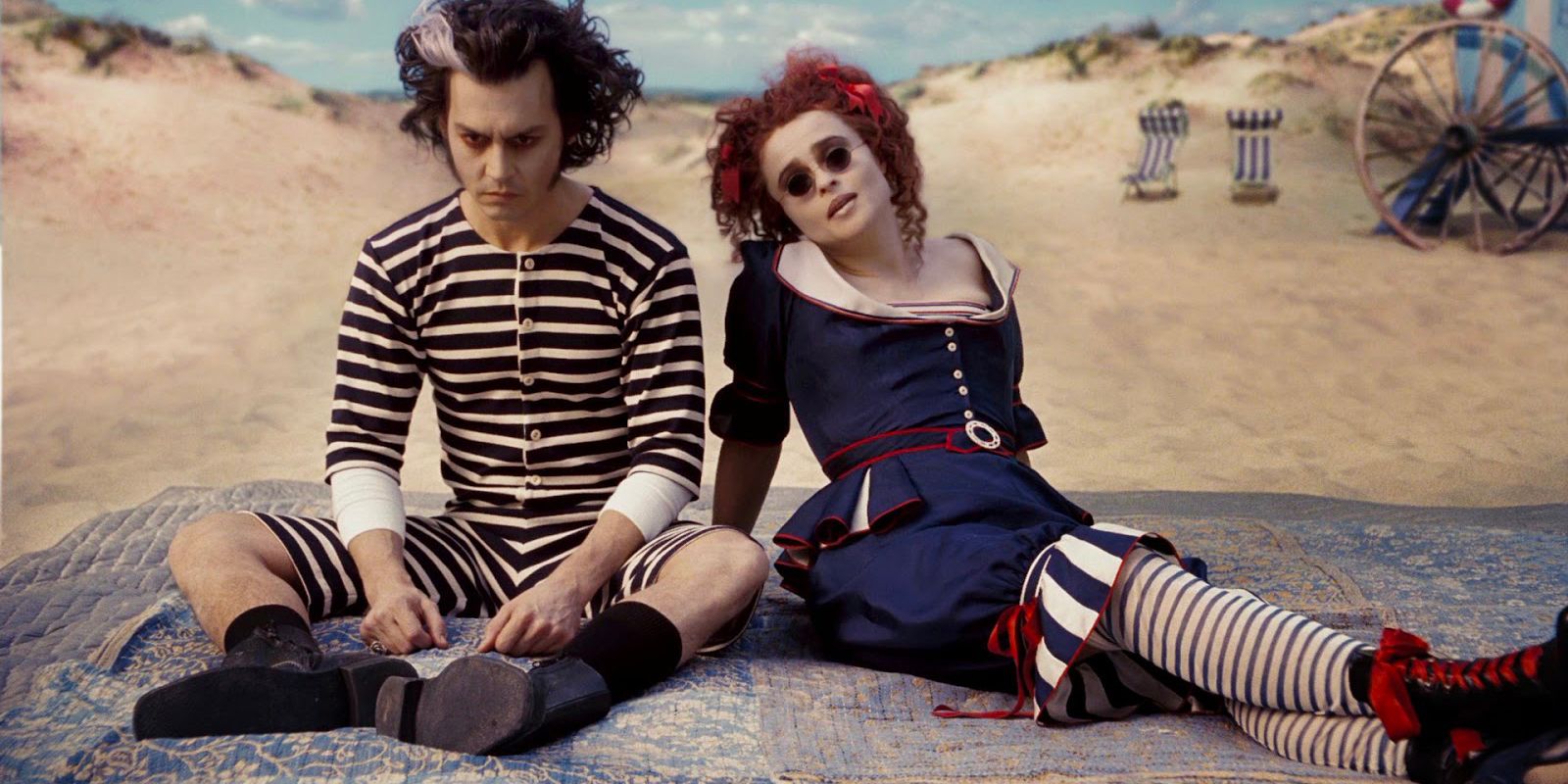

Of course, this toxicity does not apply only to the men of Sweeney Todd: Mrs. Lovett gets a whole song in which to wishcast her visions of how Mr. Todd could save her from the drudgery of selling underfilled meat pies. Todd himself is disturbingly impassive throughout the number — dropped into the lurid seaside scenes of Mrs. Lovett’s dreams, he remains frozen in an attitude of disinterest that borders on catatonia. But just as Mr. Todd and Anthony do not need Johanna and Lucy to be anything more than yellow-haired effigies that they can rescue, Mrs. Lovett needs nothing more from Mr. Todd than to be a mannequin on which she can hang her dreams of being rescued. And like Todd, Mrs. Lovett rejects genuine rescue — from Toby, whose devotion to her is genuine and absolute — in favor of the dream; as soon as Toby threatens to interfere with her dream, she is prepared to kill him, without hesitation or compunction.

Unlike Mr. Todd and Mrs. Lovett, however, Anthony gets to fulfill his dream, to save the girl. However, he also gets the opportunity to confront his own misguided motive in doing so. In what might be the movie’s most hopeful moment, he is leading Johanna out of Bedlam, telling her that they are going to Mr. Todd’s — then away, where they will be safe. What gives the scene its optimism is not its promise of a happy ending, but its injection of truth into Anthony’s fantasy. Johanna stops him and tells him, unequivocally, that things will never be okay, that her salvation is only a choice of nightmares. By refusing to endorse Anthony’s vision of himself as savior, Johanna breaks the cycle of self-delusion that traps every other character. She alone is truly able to escape, to survive the horror of Sweeney Todd.