Before hits like Slender: The Eight Pages, Five Nights at Freddy’s, and Until Dawn, two horror video game titans dominated the genre: Capcom’s Resident Evil and Konami’s Silent Hill. With 10 core games — and dozens of spin-off and mobile titles — Resident Evil is a sprawling survival-horror series that takes typical zombie fare and infuses it with bio-weapons and big pharma. With a total of 17 titles — 8 of them being core, mainline games — the atmospheric, mind-bending Silent Hill is equally prolific.

Initially, the Resident Evil series centered on the “Raccoon City incident,” during which the Umbrella Corporation, a pharmaceutical company intent on developing bio-weapons, accidentally unleashes a virus on the city’s residents, turning them into zombie-like monsters. Full of gunplay and multi-tiered boss fights, Resident Evil puts action first. Silent Hill, meanwhile, centers on “Everyman” characters, and is most well-known for its atmospheric, psychological brand of horror. The first game is set in the eponymous town, and traces typical survival-horror plot threads — a missing daughter, a strange cult, a hidden truth.

There’s no doubt that both series have broad appeal, and a lot of fan loyalty going for them. But, somehow, the most famous horror video games are also the most challenging to adapt into films or TV series. While it has long been the assumption that video game movies and series never succeed, titles like HBO’s The Last of Us have proven that it can be done well.

Part of what makes The Last of Us adaptation so successful is that its showrunners acknowledge the strengths of the new medium. While some scenes feel like shot-for-shot remakes of the game’s cinematics, others deviate to play to TV’s strengths. So, what is it about Resident Evil and Silent Hill? Are the series just not meant to be adapted into horror movies — or can storytellers take a different approach when translating them to the more passive medium of film?

Gameplay Is Hard To Translate To Screen

Interactivity is what sets video games apart from other storytelling mediums. The best games know this, and play to that strength. They use the player’s complicity in a character’s actions to deepen the story, or the level of immersion. In the original Resident Evil 4, for example, players have to stop moving in order to take aim at an enemy. What sounds like a potentially frustrating gameplay mechanic actually adds a frenzied energy to it all.

As an enemy nears, players have to make split-second decisions: keep shooting and hope for the best, or flee and take cover. The very confines of the gameplay make Resident Evil all-the-more intense, and immersive. As cool as she is as Alice, watching Milla Jovovich take out T-virus-infected hordes with ease just feels too clean, too safe. The viewer knows they're removed from the action, and the film series doesn’t do a lot to pull them back in.

That sounds like a tall order, but, again, The Last of Us makes a great case for translating heart-pounding action to the screen. In both stealth and chase sequences, the show’s crew use over-the-shoulder camera angles to great effect. Just like in a game, the viewer can’t see everything all at once — it’s claustrophobic, and it makes the viewer feel as though they’re implicated in what happens between Joel, Ellie, and the lurking Clicker.

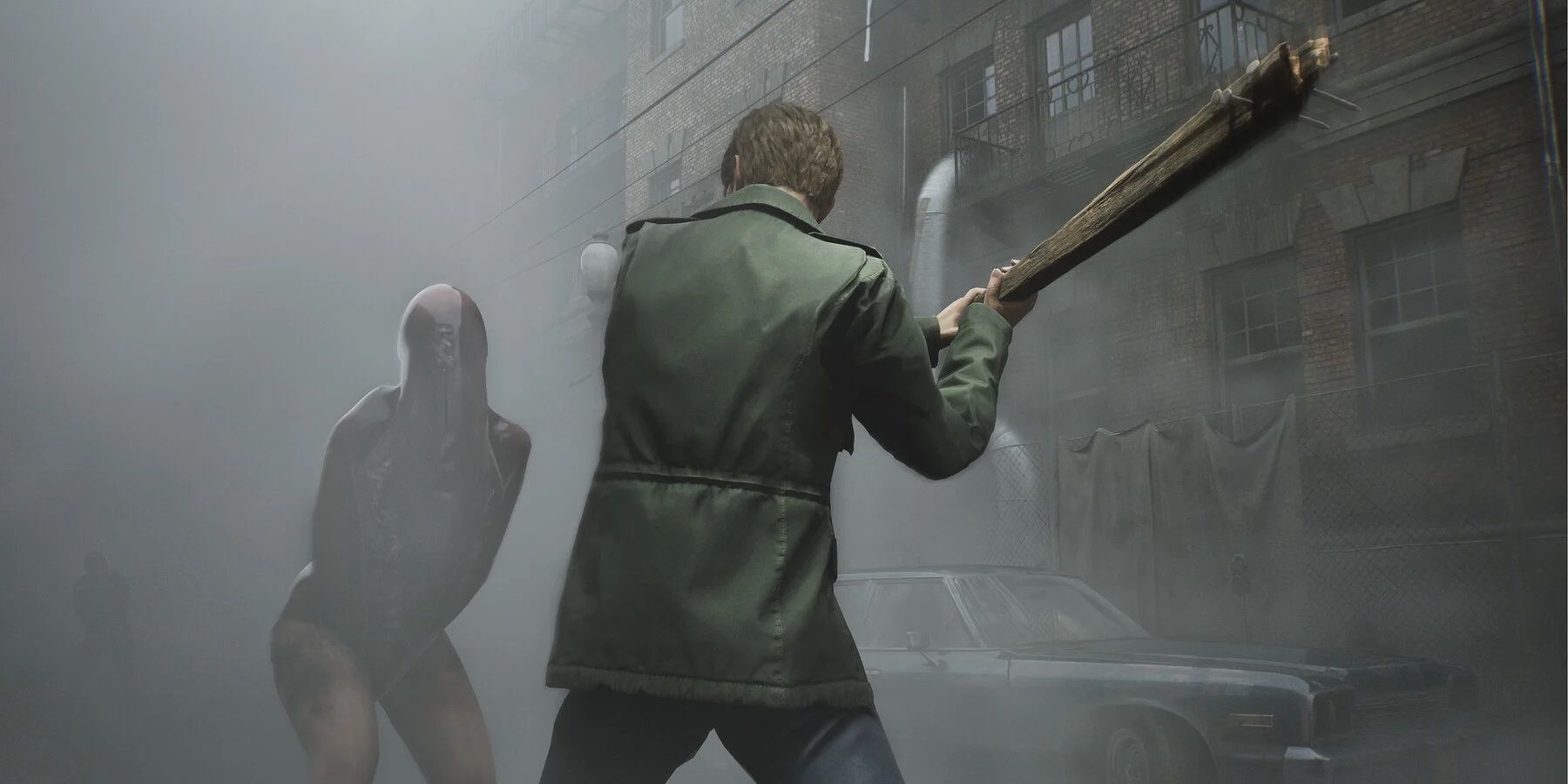

As mentioned before, Silent Hill is much more about atmosphere than action. Even so, the series’ gameplay also proves difficult to translate to a horror movie. The original Silent Hill dropped in 1999, and was lauded as a defining entry in the survival-horror genre. What made it so terrifying was, in part, the game’s focus on psychological horror, instead of shoot-em-up B-movie horror tropes. In fact, the game’s director, Keiichiro Toyama, was influenced by the films of David Lynch when creating Silent Hill.

For very different reasons, Silent Hill’s gameplay is hard to translate to a more passive medium, which is part of why the 2006 film flopped. In the first game, protagonist Harry Mason arrives in the small town while searching for his adopted daughter, Cheryl. Harry isn’t an ex-soldier or anything — he’s just a guy who stumbles upon this occult mystery and occasionally needs to rely on a firearm.

Given his inexperience, the player’s ability to target enemies is incredibly unstable. Most of the player’s time is spent solving puzzles and exploring the world around them, and, in certain areas, the camera angles shift for dramatic effect. The controller rumbles like a heart beat when Harry’s low on health, and the character’s pocket-sized flashlight illuminates very little of the dark, foggy environment. The interplay between the game’s mechanics and story are what make it so frightening.

Resident Evil: Is It Too Campy For Wide Appeal?

But it’s not just the gameplay that hampers these adaptations. For Resident Evil, part of the issue is the series’ inherent campiness. It’s over the top — just look at any boss fight. The first three games in the series, which all center around Raccoon City, are full of improbable situations, ludicrous-looking enemies, and very tropey characters. Everything feels like it's pulled from a B-movie — in the best way.

Unfortunately, the Resident Evil films series can’t strike a good tonal balance; it’s either taking the material too seriously, or diving deep into the realm of utter nonsense. As is the case in the horror video games, there are a lot of melodramatic moments, ranging from amnesia plot lines to clone reveals to long-dead antagonists returning with a vengeance. The Resident Evil films are fun in their own way, but they aren’t objectively good. The clash of tones, and the weird blend of pulling some things from the games and wholly inventing others, makes for an unsatisfying mash-up.

More than anything, the series is trying to appeal to both fans of the games and a larger horror movie audience. But these competing goals ultimately mean the franchise isn’t doing either thing well. Maybe if the films had stuck with the game’s B-movie quality, instead of trying for a self-serious action flick, things would’ve turned out better. There’s no doubt that the early Resident Evil movies go for that at times, but, above all else, the Resident Evil movies want to be cool.

When a game takes a B-movie approach, and then that gets translated back into a movie, the whole thing ends up too distilled and generic to be truly successful. And while the franchise’s number of entries speak to how fun these action romps are for audiences, there still hasn’t been a truly great Resident Evil movie.

Silent Hill's Elaborate Story Works Better In Game Format

On the Silent Hill side of things, the 2006 film adaptation might’ve been considered unsuccessful in its day, but, over a decade later, fans have a newfound appreciation for the horror movie. Instead of dropping viewers into the eponymous town, the film opens with the protagonist, Rose (Radha Mitchell), resolving to take her nightmare-having adopted daughter, Sharon (Jodelle Ferland), to Silent Hill — the place she cries out for while asleep.

Decades earlier, a massive coal seam fire wreaked havoc on Silent Hill, leaving it mostly abandoned. As Rose and Sharon near the town, they get into a car accident when Rose sees a girl in the road who looks like her daughter. Rose wakes up, alone, in the fog-engulfed dimension of Silent Hill, and learns that the town has a bad habit of periodically transitioning into a nightmarish, monster-filled version of itself.

Much like the game, a cult is at the center of all the strangeness, but, unlike the game, the protagonist is joined by others, including Anna (Tanya Allen), a former cult member who knows nothing of the outside world, and police officer Cybil Bennett (Laurie Holden). Maybe it’s the addition of other characters to Rose’s mission, but things start to feel much more “typical horror movie” and much less psychological horror as Silent Hill progresses. There are a lot of run-ins with monsters, including the fearsome Pyramid Head, but the lack of restraint makes the sequences less fraught and exciting.

Not to mention, the film tosses in a few complications, plot-wise. Although the reality and unreality of the town are an integral part of the larger Silent Hill universe, the film’s version of Silent Hill exists in a few too many iterations: the 1970s version, the present-day town, the fog-laden one, and the Silent Hill consumed by darkness. While interesting in theory, it’s a lot to move between in the span of the film’s runtime. Ambiguity can be intriguing, but Silent Hill (2006) doesn’t lay the pieces out well enough for that to be the case.

Other additions to the story only end up convoluting things further. Maybe in game format these occult twists and turns (and different versions of characters and the town) would’ve worked better. Games allow players the luxury of time; they can explore subplots and side quests at their own leisure, and not everything has to be packed into a runtime of two hours or less.

“All through the movie, characters are pausing in order to offer arcane back-stories and historical perspectives and metaphysical insights and occult orientations,” Roger Ebert said in his review for the Chicago-Sun Times. To that end, the critical consensus is that 2006’s Silent Hill is a really good-looking bad movie. For some viewers, that works. But, much like Resident Evil, there has yet to be a truly great Silent Hill movie — one that’s able to translate the nuances of the IP, and feeling of playing the game, to the medium of film.