Cinema has proven to be one of the most effective artforms for capturing paranoia. The feeling of the walls closing in and being watched from afar can be realized literally in a visual medium. Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup practically pioneered its own thriller subgenre, inspiring such taut, tense masterpieces as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and Brian De Palma’s Blow Out. The nationwide distrust in government following the Watergate scandal inspired such classic political conspiracy thrillers as The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor, and Marathon Man throughout the ‘70s.

Roman Polanski’s 1968 horror masterpiece Rosemary’s Baby has been praised as one of the most powerful cinematic portrayals of paranoia. Adapted from Ira Levin’s novel of the same name, Rosemary’s Baby tells the story of a pregnant housewife who begins to suspect that her husband, her doctors, and her neighbors are all conspiring against her and her baby.

When Polanski was offered the material, he could tell that Levin’s novel would make a great film, but there was one hurdle he couldn’t get past. The book revolves around Rosemary being impregnated with the Antichrist, and since he didn’t believe in God, Polanski didn’t feel comfortable making a movie that confirms the existence of the Devil. The director explained, “Being an agnostic... I no more believed in Satan as evil incarnate than I believed in a personal god; the whole idea conflicted with my rational view of the world. For credibility’s sake, I decided that there would have to be a loophole: the possibility that Rosemary’s supernatural experiences were figments of her imagination. The entire story, as seen through her eyes, could have been a chain of only superficially sinister coincidences, a product of her feverish fancies... That is why a thread of deliberate ambiguity runs throughout the film.”

The paranoia of Rosemary’s Baby works so well because Rosemary’s theories aren’t confirmed until the iconic final scene, so it’s just paranoia in the literal sense until the big twist ending. Throughout the whole movie, it’s entirely likely that Rosemary’s imagination is just running wild.

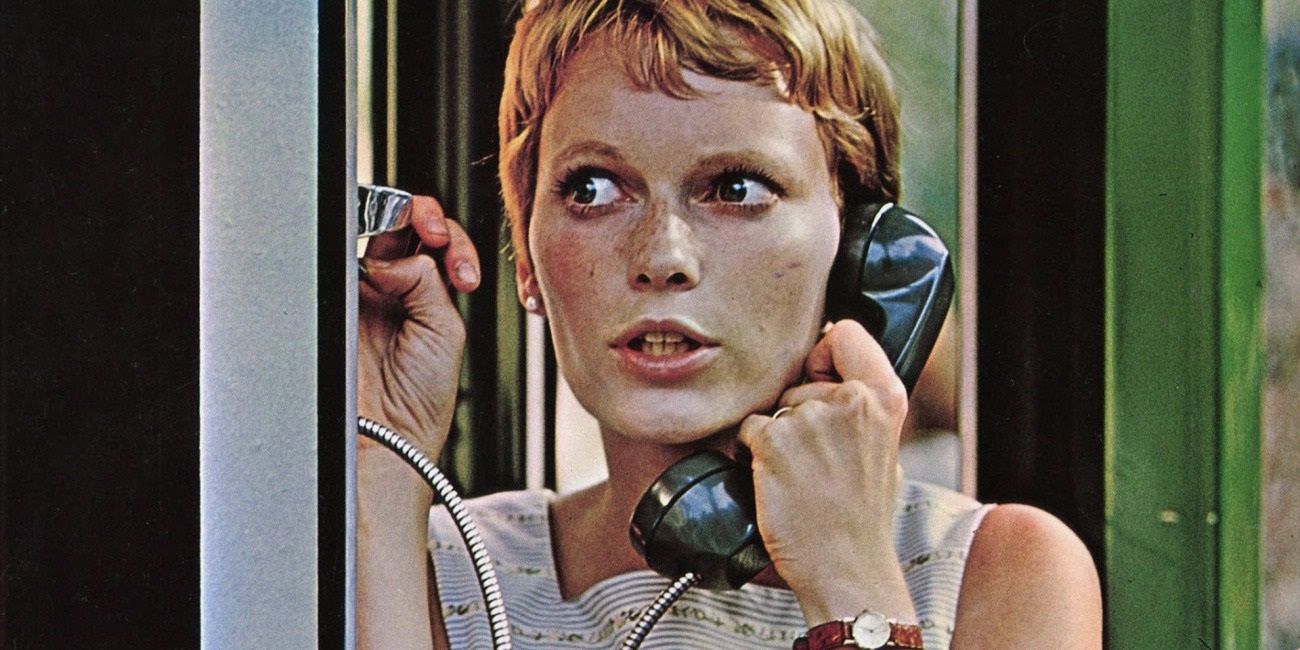

Mia Farrow’s impeccable performance as Rosemary Woodhouse, somehow snubbed for an Oscar nomination when her co-star Ruth Gordon managed to walk home with Best Supporting Actress, carries the whole movie. Polanski frames Farrow with a lot of tight closeups and only ever focuses on other characters if they’re in a scene with her, so the audience is in Rosemary’s shoes the whole time. The things that make her suspicious make us suspicious, too. We don’t get to see what her husband Guy and all the doctors get up to behind closed doors; all we see is the weird creamy medicine they keep forcing her to take.

Thematically, Rosemary’s Baby is a story about the patriarchy and specifically the control of women’s bodies. The movie explicitly referenced abortion five years before the landmark Roe v. Wade decision made it legal. Rosemary wants to take charge of what she’s putting in her body and how she’s looking after her baby, but she’s constantly undermined by a legion of male doctors. She cuts her hair at one point just to have a little agency, and Guy instantly insults her new look.

It’s depressingly ironic that one of the greatest movies about women’s liberation was directed by a filmmaker who would flee the country less than a decade later after being charged with drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl, but the movie’s message about controlling women still holds up today. Guy and the doctors continually discourage Rosemary from reading, because her research is bringing her closer and closer to the shocking truth they want to hide from her. This calls back to the fact that, historically, women have been disenfranchised by being denied education.

Like Levin’s other iconic novel The Stepford Wives, Rosemary’s Baby uses a paranoid story about men conspiring against women to explore feminist themes and women’s rights. By saving the big reveal for the ending and giving the audience no hard evidence of anything supernatural until then, Polanski made this paranoia even more prevalent – and effective – in the movie adaptation. And this resulted in one of the most haunting and unforgettable endings in horror cinema. “Hail Satan!”

Most horror movies put their protagonists in unimaginable scenarios, like being trapped on a space freighter with a bloodthirsty alien or being stalked by a serial killer in the dreamscape, but Rosemary’s Baby terrifies audiences with peculiar human behavior alone. There’s something not quite right with Rosemary’s neighbors, and then there’s something not quite right with Guy, but it’s unclear exactly what’s wrong until the very end. It’s plausible that this could happen in real life – everybody around you starts acting a little strange and you have no idea why – which makes Rosemary’s situation relatable.

With its tense atmosphere, incredible performances, and perfect pacing, Rosemary’s Baby is one of the greatest horror movies ever made. It still packs just as much of an unsettling punch over half a century later. The only downside to watching this movie is that it makes it difficult to trust people for a while.