In 2015, Universal Pictures released the horror film Unfriended in theaters worldwide. Unfriended takes place entirely on computer screens, and it was the first film made with that limitation to receive a wide release. It may have seemed like a risky investment at the time, but $64 million in box-office revenue later, "screenlife" would become the next big thing in visual filmmaking.

Screenlife as a term was coined by Unfriended producer Timur Bekmambetov, whose many upcoming projects include an adaptation of the viral horror short Don't Peek. But its origins date back to early found-footage horror such as The Blair Witch Project, a film that, like Unfriended, used viral marketing to its advantage. In many ways, screenlife is simply a successor to found-footage films, which used their intentionally amateurish, documentary-style feel to evoke reality in ways a normal film couldn't. The screenlife format expands on this by putting that "reality" inside a setting anyone can relate to. Events that would be considered commonplace in a standard horror film can be recontextualized by the eerie familiarity of a computer or mobile device. It's easy to explain why this particular film format is popular with internet-age audiences; what's harder to understand is how it manages to keep their attention despite the obvious technical restraints.

The 2011 short Internet Story, one of the earliest examples of screenlife, is the answer to that question. It’s a compelling mystery that spans multiple settings and moves at a fairly brisk pace due to its 11-minute runtime and clever editing choices. In the film, an unidentified narrator tells the story of the "Nine Grand Quest", a treasure hunt held over the internet by an entity known only by their screen name, Al1. Though the contest fails to attract much attention, a YouTuber known as Fortress dedicates themself to solving it, leading to disastrous results. The narrative hook at the heart of Internet Story is that, with all the content that exists on the internet, everything that happens in the video could have been real, and no one would have ever had to notice. Like The Blair Witch Project, it went viral on the internet because it was scaled-back enough that the average viewer could easily see it as genuine at first. It helps that both films are told in formats (documentary/narrated YouTube video) that are primarily used to tell true stories.

And screenlife isn’t really a genre as much as it is a visual medium that filmmakers use to tell stories. Due to the interconnectedness of all devices via the internet, one could even call it its own cinematic universe. The internet is a strange and terrifying and beautiful place, and many screenlife directors use the lens of film to explore its world. The most well-known screenlife films are horror, with 2018’s Searching being one of few exceptions. Horror works best when it plays on the audience’s own fears (both physical and supernatural), things they can’t escape simply by telling themselves “It’s just a movie.” Unfriended and its sequel, Unfriended: Dark Web, use very real concerns about how the internet can ruin someone’s life, an idea that was only beginning to become common in 2014, as the basis of their narratives. Psycho made people afraid of taking showers because it exposed a vulnerability to something almost everyone does frequently. Screenlife horror does the same thing.

The 2011 interactive short Take this Lollipop asked users to connect their Facebook profile to the film’s app. The user would then watch a nameless stalker view the user’s actual personal information, as gleaned from their Facebook profile, and use it to track them down. Take This Lollipop 2, which premiered over Halloween 2020 and is still online, does something similar by putting the user inside a haunted Zoom call that takes a dark turn. Films like these hold a mirror to the viewers’ own Internet activity, warning them their safety is just a click away from being jeopardized. This is still an important message, but some screenlife films, such as Megan is Missing, have been criticized for delivering it in a misleading or exploitative way. At its worst, it’s very similar to the 80s influx of satanic-panic horror, preying on misconceptions and paranoia over something people don’t really understand. But at its best, it shows both the positives and negatives of a system with almost 5 billion active users.

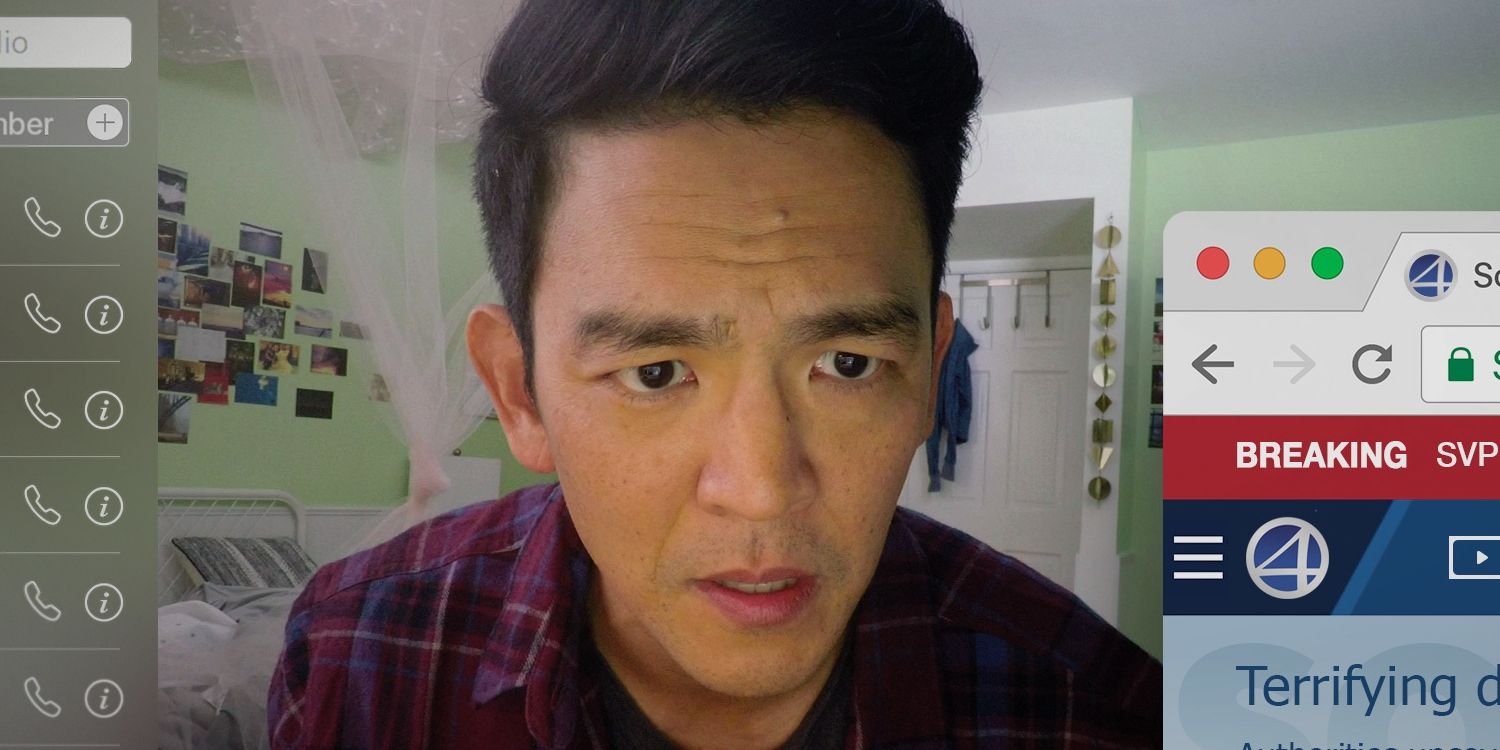

The thriller Searching is a good example of this. The story follows a man who attempts to track down his missing daughter by looking through her computer files and internet activity. As he dives deeper and deeper into the investigation, he begins to realize that almost everything he thought he knew about her was wrong. The film begins by acknowledging how important screens are in day-to-day life and showing how modern technology can both create and capture lasting memories. Instead of suggesting that screens have caused people to become disconnected from each other, it suggests that they’re merely a refuge from unspoken disconnects that already exist. This realistic portrayal is the proper way to use screenlife, since it’s not just about the found-footage-style gimmick. It’s about how its characters, and ultimately the viewers as well, interact with screens.

This sort of nuanced depiction is exactly what the screenlife trend needs to survive. It’s already experienced a revival with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused many to be stuck inside with screens as their only connection to the outside world. The critically successful screenlife horror film Host directly confronts the isolation that this can cause. But screenlife doesn’t necessarily have to pry at deeper themes to be effective. After all, when so much of modern communication is done over screens, they might also be where the best stories lie waiting, undiscovered as they may be in the perpetual content flow.