Warren Spector makes some good points about some games not making the best use of the medium, but it's time for the tired 'game versus interactive story' argument to go.

Warren Spector has never been one to shy away from speaking his mind about gaming trends. The Deus Ex creator has previously faced off against virtual reality technology, initially referring to devices such as the Oculus Rift and Project Morpheus (now known as PlayStation VR) as a fad that would only appeal to hardcore gamers. Last week, Spector took on another topic, and once more caused pause for thought.

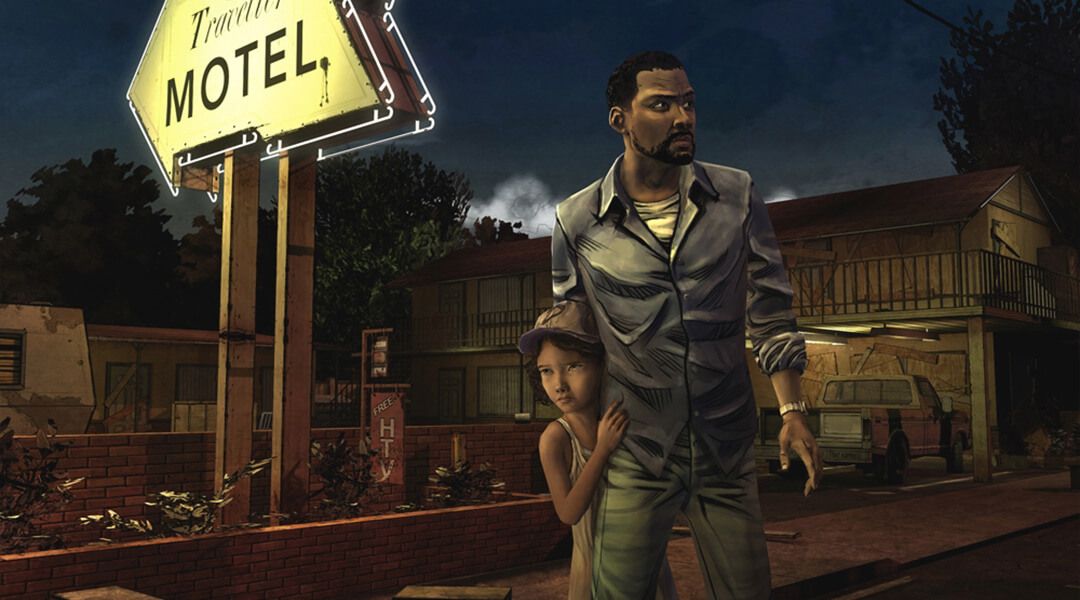

The veteran designer discussed the issue of cinematic games in a keynote at PAX Australia, critiquing the likes of the Uncharted series and Telltale Game’s The Walking Dead. In short, Spector stated that both series restricted gamers in their ability to act as a partner in any story that is told, with predefined narratives making up the bulk of any player action. He even went as far as to say to the creators of such games to “go make a movie or something” instead of continuing to work in video games.

Although Spector’s points may have been raised in a combative manner, particularly given the love for both series as standout examples of quality, modern games, I feel that there is a kernel of truth behind his points. After all, although Lee and Clementine in The Walking Dead make tough choices, all possible player acts have already been predefined and accounted for. This is even more prevalent in Naughty Dog’s Uncharted series, where the story of Nathan Drake is told with little player choice involved.

Of course, it’s increasingly difficult for developers to tell an enchanting story and deliver it alongside gameplay that allows player choice. It’s hard to marry up the urgency of the main plot of an open world game such as Fallout 3 or Skyrim with a player’s predisposition to hoard belongings or disappear on side quests. In my personal playthrough as the Dragonborn, I was more obsessed with tracking down Daedric artifacts and exploring the region than stopping Tamriel from meeting a particularly fiery end.

Sometimes, the most entertaining stories in a game can even happen through a chance encounter in single player mode, or a particularly fun multiplayer game. How many times has a gamer friend told you a story of a difficult or hilarious fight with an AI combatant in a game’s campaign, or described a thrilling multiplayer firefight? The player themselves can sometimes act as a bold narrator and find stories of their own, a point cleverly picked up in the more meta moments of BioShock: Infinite.

This makes an interesting comparison to the other side of the media coin, with the first trailer for Warcraft revealed alongside news of a Call of Duty movie universe. Both of these franchises were built primarily upon the success of their multiplayer modes, with players not necessarily picking up the games to experience the story of a protagonist with an individual struggle to overcome. It will be interesting to see how much these movies thematically fit with their video game counterparts.

One of the negative aspects of Spector’s comments, however, is the difficult attempt to define exactly what is and isn’t a video game. For all of its success in the entertainment form, winning plenty of awards and huge critical acclaim, Telltale Games have repeatedly had questions asked of their legitimacy as video game creators. The Walking Dead may be seen as one of the best video game stories around, but there are still those who don’t think of it as a game at all.

Telltale is not alone, either. Also fighting against the black mark of ‘interactive story’ are the likes of Gone Home, Dear Esther, and even such recent hits as Until Dawn. In the end, it's difficult to put a fine line in the sand to state that is and isn't a game; I've found that drama-based games such as Facade can offer the player more chances to affect the outcome of any scenario than many shooters.

There's one other personal bugbear I have with Spector's comments, and it comes down to a desire for games to make the most of "collaborative storytelling." Although this can definitely deliver some fantastic games, it also gives an unnecessary restriction to gaming in general, even if it's seen as an ideal to achieve and not a necessity. I feel that Spec Ops: The Line was one of the hidden gems of the last console generation, with a story that made the most out of a linear plot without player collaboration involved.

Without giving away too much of the plot, the user is forced to commit a heinous act, forcing the player to think about those actions in other games they have played. If the player was able to have some kind of collaboration in this respect, then the entire point of the game would have been lost. Indeed, I feel that one of the flaws of the title is that the player is given some kind of control over the main character's outcome in the game's finale, when a developer-defined choice could have been much more powerful.

In short, one of the things I love about video games is the sheer scope of the entertainment form. A creator's imagination is not restricted by a defined list of what should and shouldn't be in the game. With video games forever growing in their scope and design, perhaps it’s time for the definition of what counts as a ‘real’ game to be loosened.