Fans of classic horror have probably heard, at least in passing, of the film Cannibal Holocaust. It came out in 1968 and was practically born into infamy due to its extreme use of violence and gore. While it isn't as controversial today as it was 50 years ago, it's still the subject of many a debate. But what makes this classic "video nasty" so discussed (and so disgusting)? To discover that, the best place to start is with the director, Italy's own Ruggero Deodato.

Deodato's mentors didn't just direct films; they also directed the course of his career. Sergio Corbucci, for instance, made brutal Western flicks such as Django. He was a bona fide boundary pusher. And Deodato, who served as co-director on Django, learned a lot from the elder auteur. Deodato went on to work with a mix of genres, such as peplum (also known as sword-and-sandal). But his singular style is most clear in his violent dramas and thrillers.

While he'd dealt in horror before, Deodato's first foray into truly brutal cinema didn't come until 1976. The crime drama Live Like a Cop, Die Like a Man marked the first time Italian censors cut his work. But he only grew bolder, with his next film, Jungle Holocaust, setting the stage for what was to come. It's a fairly standard cannibal horror tale, though, once again, its extreme violence raised some eyebrows. While his films were hardly well-known, Deodato was beginning to stand out.

1979. Contacted by producers who want him to make another cannibal picture, Deodato begins looking for a suitable filming location. At an airport in Colombia, he meets a man who is working on a documentary film. Hearing of Deodato's plight, the man suggests he film in the city of Leticia. It has a lush rainforest and a tropical climate. In fact, it's a perfect match for the Amazon, where Cannibal Holocaust takes place.

Deodato conceived the film as a satire of how the media uses shock value to its own advantage. During the production of Cannibal Holocaust, a guerrilla group called the Red Brigades was terrorizing Italy. Deodato noticed that TV news coverage of their attacks leaned heavily into sensationalism. His film plays into this: its horrors are not what they may appear to be at first.

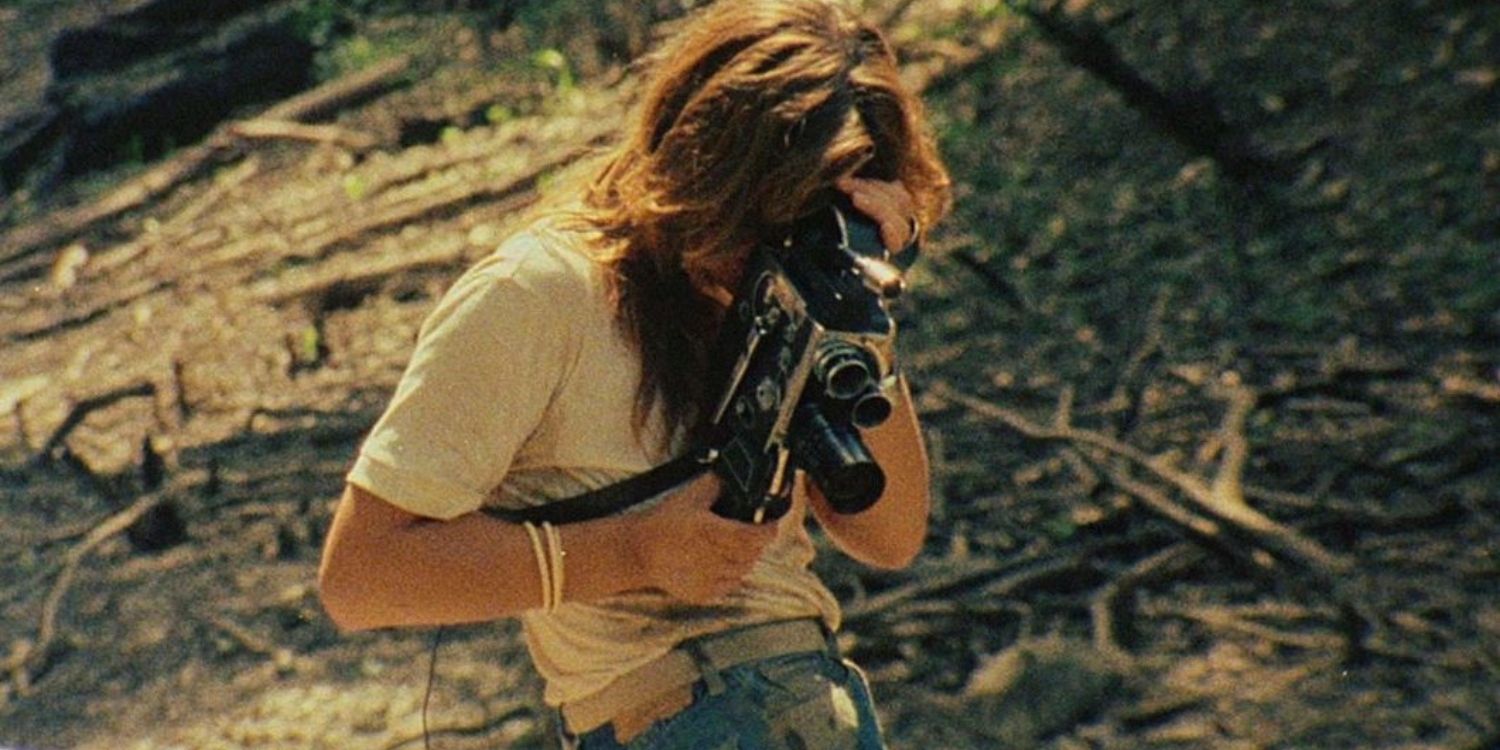

The story follows a missing film crew and the rescue team that tries to track them down. The film crew was shooting a documentary on cannibal tribes when they disappeared. The military intervenes and takes a local tribe member hostage as a means of negotiating for the crew's safe return. Upon his release, the members of the rescue team manage to earn the natives' trust. But the filmmakers? They're still missing, and it seems they did something to upset the tribe.

Up to this point, the film seems like it's setting up a recognizable "something bad's gonna happen" twist. But though something bad does happen, it's much more anti-climactic than expected. The search party discovers a shrine with the skulls of the missing film crew. They barter with the tribe in exchange for the crew's film reels, and make it out alive. But there's a brooding horror that has been lurking throughout this narrative. And Cannibal Holocaust begins to communicate that horror as it turns into a found-footage movie.

The first "found-footage" movie was Shirley Clark's 1961 film The Connection, which follows a director taping drug addicts. In a way very similar to Cannibal Holocaust, it delivers its social commentary in mockumentary fashion. But even 20 years after that, this was still a fairly new genre. So when Deodato's film came out, people thought he had conned them into watching a snuff film. The actors were unknowns, and to keep up pretenses, they made no media appearances to promote the film. So for all the audience knew, they really could be dead. And if they weren't, how could he have filmed the graphic scenes of torture and violence?

Speaking of those scenes, the film ends by revealing that the filmmakers themselves were the true monsters. They terrorize the natives to get better footage, culminating in truly evil decisions born out of that same desire. These revelations intertwine with a subplot involving studio execs who want to use the shocking footage for their own gain. Upon realizing its true nature, however, they order it destroyed. The film ends with the leader of the rescue team musing "I wonder who the real cannibals are."

Sergio Leone, creator of the Spaghetti Western, wrote to Deodato after seeing the film upon its premiere in Milan. He called it a "masterpiece", but added "everything seems so real ... you will get in trouble with all the world." Ten days after the premiere, police arrested Deodato on obscenity charges. And by the time he appeared in court, the charges had extended to include murder as well. In a truly cinematic moment, Deodato explained to the court how the film's special effects worked. He also provided proof of the actors' well-being. Needless to say, the court dropped all charges against him. But they ended up banning the film anyway, albeit for a completely different reason: animal cruelty.

Animal cruelty is a monstrous thing. The killing of real animals is one reason that many feel Cannibal Holocaust is ultimately a hypocritical work. It's the only thing Deodato regrets from the film's production. Though an entire article could come from the many ways in which he treated his actors poorly. Or how, despite its message, the film depicts its (unpaid) native extras in a racist manner throughout.

One could argue that these faults only prove the film's point, however. Media itself is the cannibal, feeding on the dead. Whether by a journalist or a film director, the quest for shocking "realism" often triumphs over good sense.