Although the rise of so-called “elevated horror” is quickly saving the genre, horror cinema risked losing its relevance a few years ago when its output devolved into a slew of derivative “torture porn” thrillers with excessive gore and no artistic merit. These movies were so desperate to push the boundaries of previous horror films that they desensitized contemporary audiences to a lot of great older movies that exercised restraint and used sharp cinematic technique, not a bucket of fake blood, to scare audiences.

But the desensitization of modern horror audiences has only served to highlight the merits of the true horror masterpieces that have stood the test of time, like Ridley Scott’s Alien and John Carpenter’s Halloween. These movies would be considered tame by today’s standards, but thanks to their directors’ tireless efforts behind the camera, they remain timeless horror gems that still have the ability to terrify audiences half a century later.

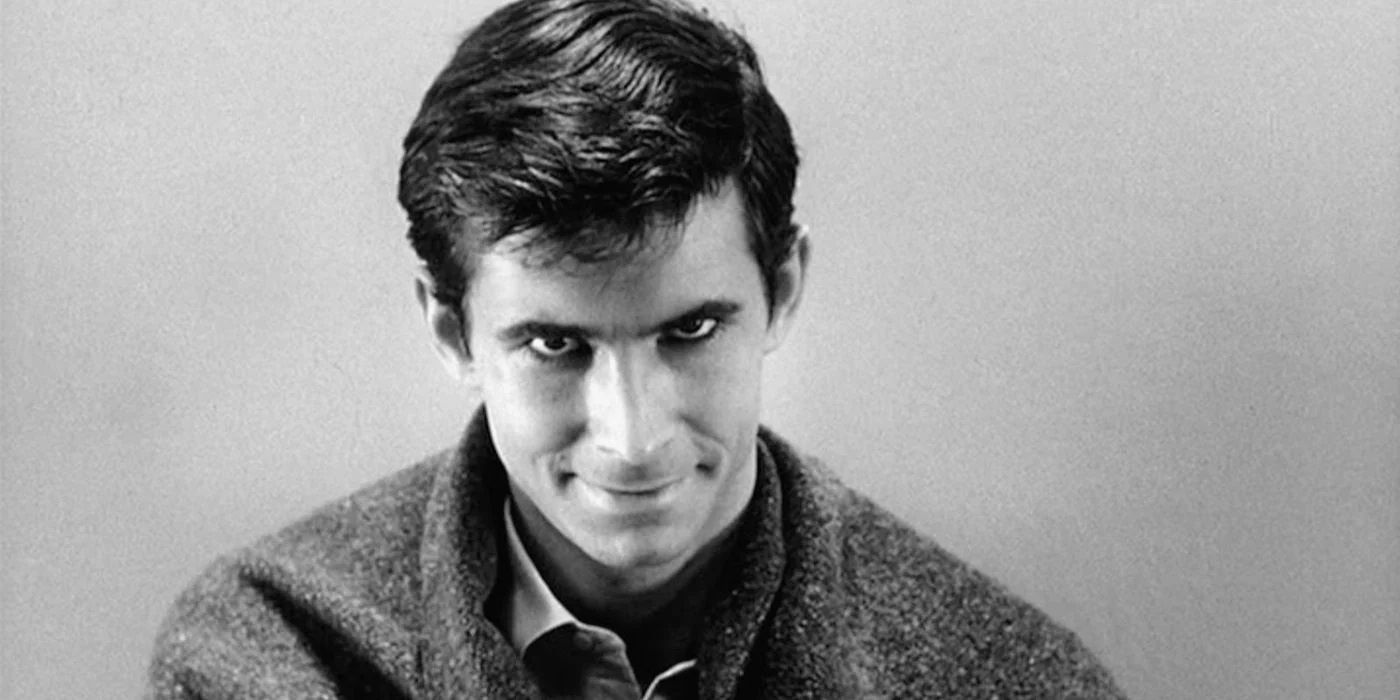

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is one such movie. It remains a revered classic that still has the ability to terrify modern horror audiences with its harrowing twists, iconic villain, and groundbreaking filmmaking techniques. It may be over 60 years old (if it was a human being, it would be making retirement plans), but Psycho still holds up next to any horror movie from the past decade, because its genius relies on a few timeless elements of terror. Bernard Herrmann’s tense score and Anthony Perkins’ unsettling performance as Norman Bates will never lose their impact.

Like a lot of great horror movies, from Alien to Audition, Psycho waits until its shocking midpoint twist to solidify itself as a horror movie. Just as Alien starts out as a sci-fi movie and Audition presents itself as a melodrama about grief, Psycho sets itself up as a crime thriller about a woman embezzling money from her rich boss and going on the lam with it. But it quickly turns into what has been described as the first slasher when she stops off at the Bates Motel and encounters the walking, talking embodiment of the Oedipus complex.

In 1960, audiences were blown away by Psycho. Janet Leigh was one of the biggest movie stars in the world, so when her character was murdered in the shower halfway through the movie (a gambit that has been replicated to much lesser effect by a bunch of movies since), contemporary audiences were genuinely shocked. Today, it’s not so easy to have that effect on audiences, because the shower murder has been parodied by everyone from Mel Brooks to The Simpsons, and Janet Leigh is no longer a world-renowned star.

But after spending an hour getting to know Marion Crane and following her journey deeper down the rabbit hole of crime, the shower murder still comes as a shock. The scene is pieced together so masterfully that it overshadows any ridicule and the audience gets swept up in Hitchcock’s meticulous cutting and Herrmann’s piercing violin screeches. After Marion is murdered, leaving the movie without a protagonist, the camera scrambles to find a new focus before settling on Norma Bates’ creepy house up the hill. Suddenly, a run-of-the-mill noir becomes a spooky murder mystery.

Throughout his legendary career, Hitchcock defined a lot of the visual storytelling techniques that are commonly used by filmmakers today. Along with Kurosawa and John Ford, Hitchcock is one of the pioneers who laid the groundwork for modern cinema and influenced basically every single filmmaker that came after them. From Vertigo to Rear Window, The Birds to North by Northwest, Hitchcock proved time and time again that he’s a master of telling stories with sounds and images, and that he can bring real artistic value to a thrilling genre movie. This sensibility is perhaps most prevalent in Psycho.

Some modern moviegoers are put off if they find out a movie is shot in black-and-white. (Other, more mature viewers can deal with the absence of color for a couple of hours.) Hitchcock shot Psycho in black-and-white, but not out of technical necessity. He produced the movie well into the color era; he shot it in black-and-white as a stylistic choice. The gloomy black-and-white composition makes the movie’s most unforgettable images, like Norman standing in the basement doorway in the climactic scene, even more unnerving.

When Hitchcock made Psycho, horror movies had settled into a trend of supernatural tales of the macabre. Psycho created a wave of startling realism in horror cinema, with movies like Peeping Tom exploring haunting premises that could actually be real. There’s nothing supernatural about Norman Bates’ blood-soaked reign of terror; it’s just disturbing human behavior. While Herrmann’s score takes over a lot of the movie’s soundtrack, Hitchcock also found plenty of uses for a filmmaker’s greatest asset in the sound department: silence. In certain scenes, an eerie silence grounds the reality of the situation. This can be seen when Norman dumps Marion’s corpse in a lake in dead silence in the middle of the night and, for a second, it seems like her body might not sink.

Despite Psycho’s reputation as one of the greatest thrillers ever put on film, a lot of modern audiences with a modern sensibility might never check it out because it’s too old and slow-paced and shot in black-and-white. But Hitchcock’s masterpiece still holds up today. It’ll be more terrifying to a new viewer than any new horror movie coming out this year.