Akira needs no introduction. As one of the most popular anime and manga series ever made and one of the biggest influences for the cyberpunk subgenre of science-fiction, the 1982 manga and 1988 anime film are staples of not only Japanese media, but popular culture in general.

With a new anime series for the franchise in development by Otomo as well as an upcoming live-action film from Taika Waititi, it’s worth a look to see how a cult-classic mangaka also pivoted to becoming a legend of anime film.

Katsuhiro Otomo’s Inspirations

Akira’s director Katsuhiro Otomo harbored an appreciation for manga at an early age. Growing up in Miyagi Prefecture in the rural Tohoku Region of northern Japan, manga books provided a major source of entertainment to break up the monotonies of small-town boyhood. Likewise, the two manga he’s since reminisced as particularly formative during this period, Osamu Tezuka’s legendary Astro Boy and Tetsujin 28-Go, would underscore much of his interest both in sci-fi and in the appeal of sprawling urban metropolises far-set from his own small-town life.

By the time he was in high school, Otomo’s interest in manga had taken a more creative turn. He began illustrating his own work, and soon after graduating high school he was able to make the big move to Tokyo and work for the legendary manga publisher Futabasha, initially working on a manga adaptation of a short story by the 19th-century French Romantic writer Prosper Mérimée. By the age of 25, Otomo had begun working on his own independent film projects aside from the manga work. Like Ralph Bakshi or Quentin Tarantino, Otomo never went to a formal film or art school beyond high school.

Akira: The Initial Manga Series

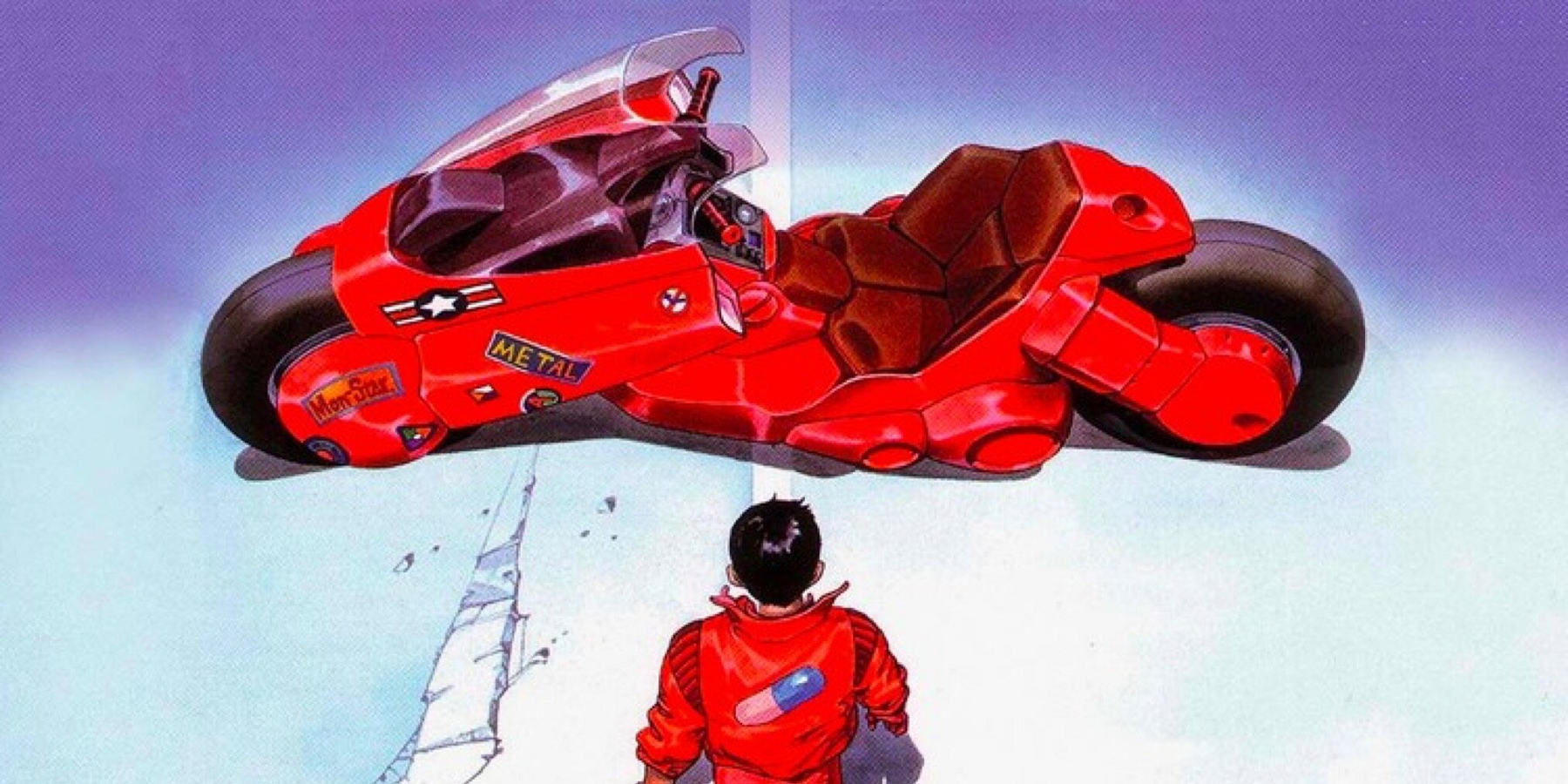

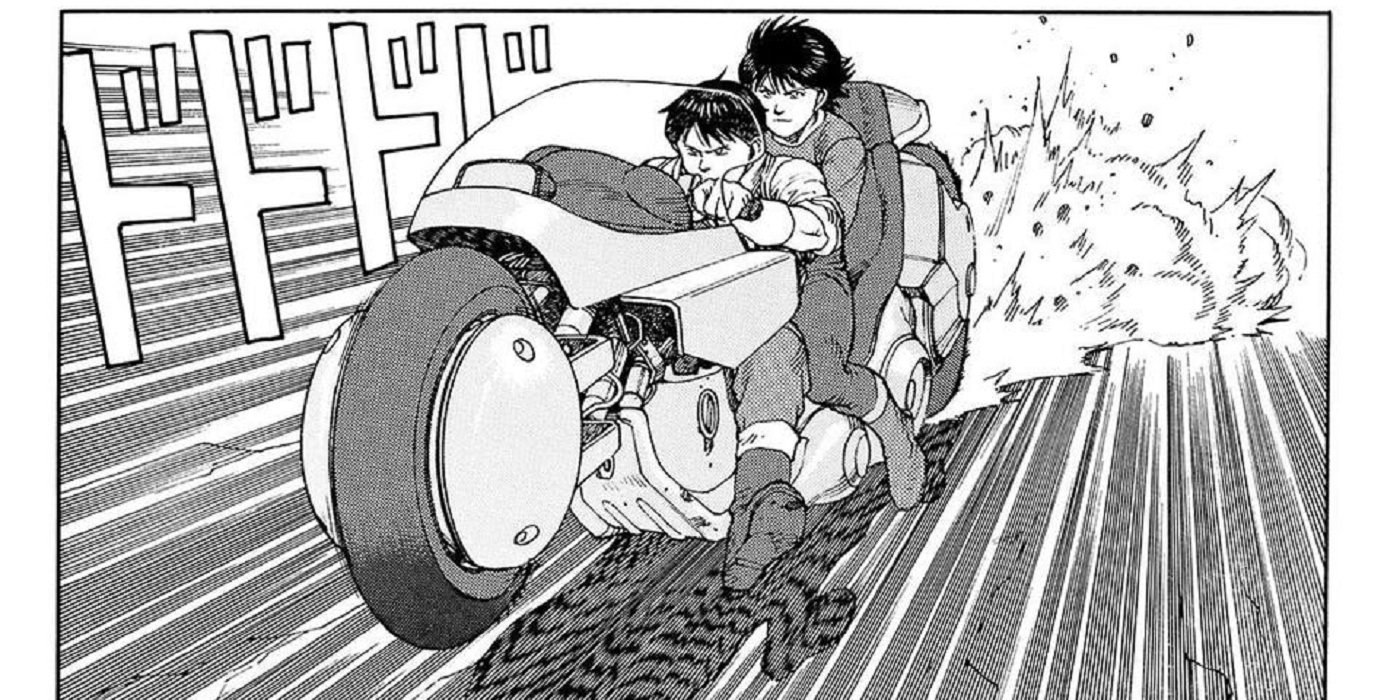

After working on a slew of different manga series and his own side-projects in live-action film, Otomo was approached by the manga publisher Kodansha to write a science-fiction series for one of their young-male publications. Under the impression that this project would just be a brief newspaper comic, Otomo created Akira, a dystopian sci-fi set in a futuristic 2019 Neo-Tokyo. Akira served as a spiritual follow-up to many of the plot elements Otomo was unable to include in his earlier 1979 sci-fi manga effort Fireball, focusing on young rebellious characters that would be echoed in Kaneda and Tetsuo.

Akira quickly outgrew the simple production order, becoming a staple of Kodansha’s manga lineup. Otomo would frequently put great care into the presentation of each of the manga’s volumes, to the point where he was known to make tough cutting decisions at the max-limit of each volume and even wear out some of Kodansha’s publishing equipment trying to capture the perfect colors for the series’ covers. It was this perfectionist discipline that spurred Otomo to pursue the most ambitious project of his life, and one that would rocket him from a successful manga artist to one of the most legendary names in pop culture inside—or outside—of Japan.

How Otomo Got to Direct His Own Adaptation

After the constant work of the serialized Akira, Otomo first began to direct anime with short film segments in the 1987 anime anthology films Neo-Tokyo and Robot Carnival. It was around this time that Otomo was approached for a potential anime adaptation of his magnum opus, to which his interest was tempered by an insistence on retaining his own creative control. Because of his previous experience in anime directing, it was a logical step that Otomo would be qualified to direct an animated adaptation of his own project. And so, with negotiations from producers Ryōhei Suzuki and Shunzō Katō, the film was funded with investments from “The Akira Committee”—a large and loose conglomeration of production outfits ranging from the publisher Kodansha, to the legendary Japanese film studio Toho and many others. The ultimate budget for Akira was 700 million Japanese yen, making it the most expensive anime feature ever produced up to that point (that record would only last a few months, later being beat by Studio Ghibli’s My Neighbor Totoro in 1989).

Much like the effort Otomo put into his manga volumes, Akira is a visual masterpiece that highlights a lot of the manga’s story in a large runtime. While the film’s plot can at times feel a bit rushed to accommodate as much of the manga’s storyline as possible, its art quality has earned it a reputation as some of the best-made animation of all-time.

Akira’s Legacy in Anime and Sci-Fi

Akira quickly made back its budget and became one of the most successful Japanese films of 1988, later spawning a cult classic following in other parts of the world and being a major influence on the cyberpunk subgenre that continues to this day. The film’s images of a seedy, seemingly endless cityscape influenced countless urban-sci-fi creations, and the film’s fluid and precise animation opened up the door for increased attention on Japanese animation for international audiences in the 1990s. In fact, Akira’s technological grit became such an important symbol of Tokyo’s identity in the public consciousness that there were plans to use its aesthetics as a significant part of the opening ceremony for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, before the games were ultimately pushed back a year and significantly scaled-back because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The success of Akira didn’t shake Otomo from his roots in manga and animated anthologies; he went on to produce the additional anthologies Memories (1995) and Short Peace (2013). In addition to his upcoming return to theatrical directing with the forthcoming feature Orbital Era (also based on one of his manga series), Otomo is since also in talks to further adapt Akira in series format. These projects, in addition to the live-action Akira film currently underway at the helm of Taika Waititi, are proof of continued interest in one of anime’s most influential properties—a juggernaut that is only possible thanks to the protean work ethic of its creator.