Game Rant recently got a chance to sit down with Paweł Miechowski of 11-Bit studios, the development team behind hits like This War of Mine and Frostpunk, as well as the publisher for a variety of interesting titles from Moonlighter to Children of Morta. Our interview marked the tenth anniversary of Paweł's tenure at 11-Bit, so we had a lot of questions about the company's growth over time and how it came to be known for such subversive and even groundbreaking titles. Our guest was more than happy to share, even delving into some teasers for new upcoming projects.

This interview covers the upcoming Frostpunk expansion On the Edge, 11-Bit's famous approach to piracy, the studio's tactics for flipping genres on their heads and creating tough decisions, upcoming projects, and ten years of change in an exceptionally innovative development environment. The interview was quite lengthy, so some portions have been altered slightly or shortened for ease of consumption.

Q: I noticed that 11-Bit focuses a lot on accessibility; a lot of things are multi-platform. Is that part of a mission, or just a financial concern?

A: If you ask me about accessibility understood as for people with disabilities, then yes. I had the privilege to meet Steven Spohn from AbleGamers 9-10 years ago, and he practically told me what would be the guide to make games more accessible. So we try to include features that make games more accessible for disabled gamers. But in terms of platforms, that’s more business. When we were a smaller company that was important because more revenue streams and more audiences. Nowadays it’s a question of reaching audiences.

Q: While I was researching 11-bit, I noticed a story come up again and again about free copies of This War of Mine provided as a response to piracy. Is there anything more to that story?

A: The idea was loosely based on an idea from another Polish developer, who noticed that his game was not selling well, but was insanely popular on pirating sites. He actually bought an advertisement on the site to encourage people to buy the game, and his sales skyrocketed. So, we saw a similar trend with This War of Mine; it may have been number one on certain pirating sites the day of its release. We said we’d rather not fight piracy, so we gave free Steam keys and asked people to retweet or do any support they could do. That news was insanely popular all over the internet and it turned out very well.

It’s not an official statement, but I think we’d rather not fight piracy, because people who consume a lot of games are the ones who buy the most games. Sometimes they can’t afford the game. It’s not good to pirate, but sometimes that’s the only way they can try it, and then if they end up playing it a lot they will buy it anyway. There was a study- I believe done by an American university, but it showed that those who consume the most pop culture through subscriptions and cinemas are also the ones who pirate the most. There is a straight correlation between those who illegally download and those who buy the most legally, because they are just the ones who consume the most of that culture.

I understand that there might be students who really can’t afford games. But later on they finish university, and they can buy games. Poland is very specific on that matter, because up to the 90s we didn’t have a proper copyright system for games, and piracy was essentially legal. I remember in high school the only way to play games at all was pirating stuff that came from the West. The legal market was only born in the late 90s. So people might not be able to get a game, but they will when they can.

Q: It seems like a lot of the games that you have made or published take a normal, familiar formula and flip it on its head. Frostpunk is a survival-based city builder, Anomaly is a flipped tower defense. Moonlighter is the other side of being an adventurer. Do you guys go out looking for a formula to flip, or is it something that happens more naturally?

A: Definitely at first our idea was to flip genres upside down, or to bring something new to established genres. This was our clear policy: mix or turn genres upside down. So such was Anomaly, or Sleepwalker's Journey, which was a platformer where you played as the platform, not the character. After we started to work on This War of Mine, we started to think about what would be the next step in our vision. This philosophy is still evolving and growing, but it came that we should have a clear vision of what we want to make and achieve, and such way was born what we call “meaningful entertainment.” Rather than flipping or combining genres, now we think about topics we can discuss in a game.

Moonlighter is a great example. On the one hand it is a cool RPG action game, but the core idea is that it is about a man who wants to fulfill his dreams. He’s the shopkeep, but his dream is to become a warrior, and that’s exactly what the game is about. Or Children of Morta, a game about how family bonds can be strong, or This War of Mine, a game about how people suffer in war, and how war can be perceived differently. And Frostpunk, a game about power and responsibility. So we see meaningful entertainment as games wrapped around one powerful idea, and we’re going further in that direction.

Q: Games are the only media in which the consumer gets to choose what happens. It seems like you guys really try to make those choices difficult, and make the player think about those choices. When you’re going for a message in a game, do you start with a couple key dilemmas or choices from the very beginning of development? How do you design choices to be tough?

A: We had an internal discussion recently about ‘what is the language of games?’ Like you said, in movies the language is pictures and sound and story, but in games the language is interaction. The fact that you as the gamer are a storyteller thanks to the choices you make allows you to shape the story through those choices. We think about what kind of environment we should create in which the player is confronted with different dilemmas. The bigger, the more free the environment the better. It’s very important that the environment cannot be judgmental.

It needs to be free, and free in the space of good and evil. The game cannot moralize for you and tell you what is good or bad. If you do something wrong the only way to judge yourself is to feel remorse. It’s a very strong emotion, and games have this brilliant space that allows you to make those choices and think about them. The bigger the project becomes the more we think about different dilemmas. It’s a fascinating topic, because you are combining music, psychology, art, programming, and so many things into one that becomes a game.

Q: It seems like 11-bit is set apart from other developers and publishers because of that focus on those powerful messages. Is that a workplace culture? How do you get so many people to focus on that?

A: I think it started with This War of Mine. We had a prototype called Shelter. It was a good prototype, but it lacked those emotions. My brother came up and said: 'let’s make a really serious game about regular people like you and me trying to survive war.' We were struck by the idea, and decided to do it no matter what. It would be risky, but it was such an inspiring idea. We got a spark. That was the first step to that philosophy for creation. And our marketing director had a lot of ideas on how to build on that and make it a vision that drives the team. So the team grew from there, but people who joined all share that mindset.

Q: As a company that was an indie developer, what is it like to publish similar games?

A: We got a lot of experience on how to do everything from A to Z. It was then a natural idea to create an environment made up of multiple developers and become a publisher. We have a different approach because we know what a developer needs, and what a publisher should deliver. We need to fall in love with the developer’s vision and truly understand it so that we can help to promote it, but not mess with it. It’s like that with Digital Sun, the guys behind Moonlighter. We’re actually working with them on another project, but it’s a secret.

Q: Obviously it’s exciting to see a company and a team grow, but were there any growing pains during 11-bit’s expansion?

A: Definitely. The first big problem is communication. Up to 70, you can recognize everybody by name, and everyone is a friend or colleague. Now we’re 140, and sometimes it can take a while to recognize new people. You also lose a flat structure. Beyond a certain point you need vertical structures, senior managers, individual teams like marketing, QA, designers, and so on. But of course, if you look at huge projects like Red Dead or Ubisoft games it’s attainable.

Q: Thinking about those big triple-A games, do you think that it’s possible for games like yours with challenging emotional subject material and difficult choices to reach the scale of games like Assassin’s Creed or Red Dead? Or are they too challenging to have wide appeal?

A: Definitely. I think there is room in this industry for everything that is simply good. A really great example is another polish game; The Witcher. A really massive, successful game, yet still they managed to squeeze a lot of really interesting and mature stories into that universe, along with really tough moral choices. It’s no wonder to me why The Witcher was such a success. It has that unique vibe with its mythology and art, moral choices, rich story, and yet we’re talking about a huge triple-A production. Another example is Hollywood movies. There’s room for both the Avengers and The Irishman, but both can be a huge success. It’s a hard story to digest, but at the end you say “wow.” So yes. We can and we will have amazing triple-A’s with a lot of those mature stories. I expect it.

Q: What has been the most exciting moment in the last ten years of 11-bit studios?

A: It’s interesting you ask that, because officially my ten year anniversary is today. I think This War of Mine was a great moment. We knew when making the game that we were doing it in the right way. We knew it was risky, but we knew it was done in the right way with the proper respect to the topic. We still didn’t totally expect the success, and the media support was insane. We were a really small team from Poland and suddenly the world was covering our game.

The New York times, LA Times, Washington post, Die Welt in Germany, the Guardian in the UK, all these mainstream places- we were really surprised. They were praising us for our brave approach, showing war not just from a soldier's perspective like in Call of Duty. The launch was such a thrilling moment, it was amazing. Then after that the Frostpunk launch was great. We had a bit of a crisis, thinking we had made such a different game, and not knowing what was next. But it was a small crisis because our board members just told us, 'Guys, we are pretty good developers. Let’s just focus on doing our best.' Then the launch went really really good, so I think the stress was pulled out from us.

Q: What are you most looking forward to now?

A: Well, we have three projects in the publishing division, and three in the internal division. I’m definitely looking for one, in the publishing, that’s close to my heart. It’s not a depressing game like This War of Mine, it’s really joyful, but it has some interesting problems to tackle. A lot of stuff is confidential and I cannot go into, but we do have the coming expansion to Frostpunk which we just announced today. It’s called On the Edge.

Q: That sounds phenomenal, we'll be looking forward to it. Is there anything more you would like to talk about?

A: Sure, on the topic of games with difficult moral dilemmas, some people don’t need or want to go really deep in, and that just comes down to preference. However, the critics praise the parts that appeal to your humanity, and put you in a situation where there is no ideal way out. If you think about it, it’s like a Greek tragedy; whatever option you pick it will end poorly. Sometimes in life people are put in exactly that sort of situation, like the well know trolley conundrum. Life is such an environment. We like to recreate those, and even push further like in Frostpunk. When we have an idea like Frostpunk: 'let’s make a game about power,' the point isn’t just that there are only bad rulers on the earth, but that it’s unique to rule, make decisions, and feel responsible. We want to put people in the 'what would you do if...' scenario, and apparently there’s a ton of gamers who like to ask themselves those sorts of questions.

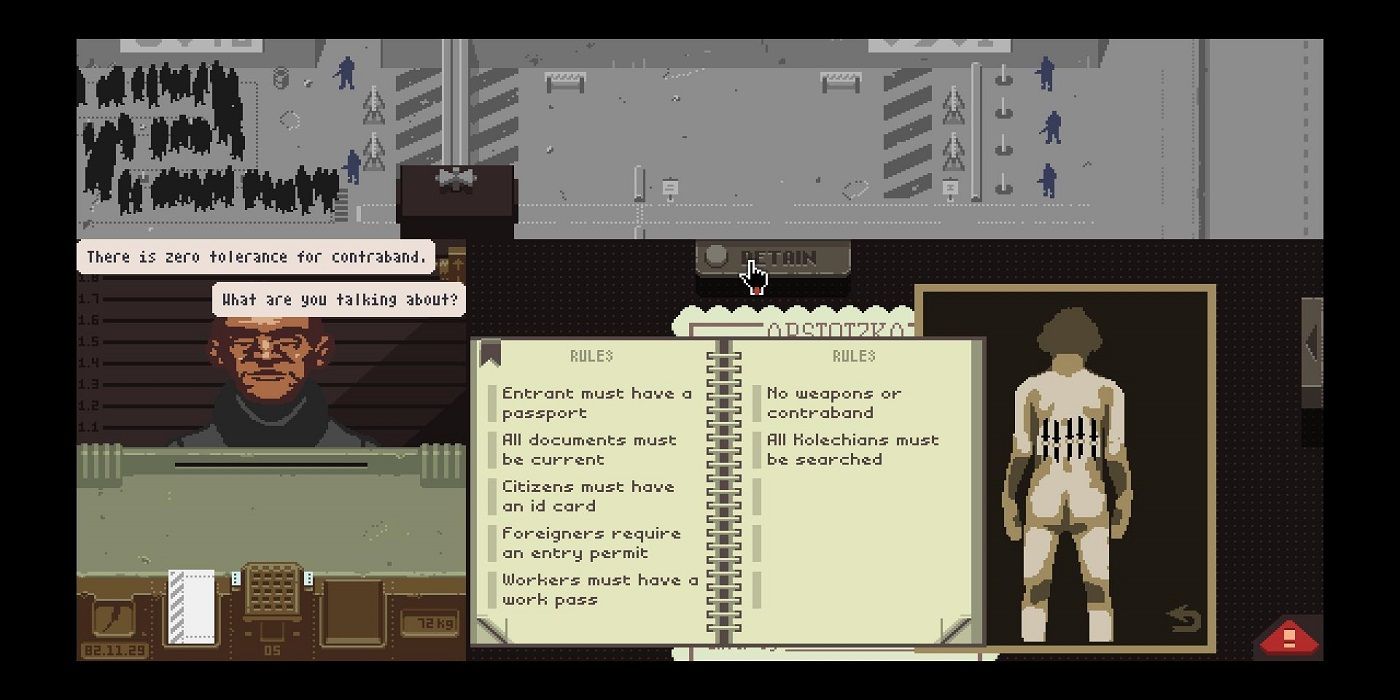

I once met Lucas Pope, just after releasing Papers Please. That game was a brilliant example of how you can tackle a player’s emotions by putting them in front of such dilemmas. Do I take the bribe to support my family, do I put myself at risk of losing my job? It was the perfect example of a game that was mature enough to tackle those problems.

Q: From a design perspective, there can be a strategic use of something being not fun to make the game as a whole more fun. It might not be fun to make a tough decision, but it makes the game itself fun. Does 11-Bit ever think like that?

A: you need to feel the weight of the decision, and the design has to be well executed. The designers have to think about the emotions they want to spark at the end. When it comes to challenge, there’s satisfaction, and when there’s frustration there’s catharsis. There’s satisfaction in knowing you made the right choice morally. The emotions can be a bit engineered in a game, and designers have to specifically think about how to achieve a feeling. It takes a lot of iterations and testing.

GR: Well thank you for your insight, but that’s all I have prepared. It’s been great talking.

P: Thanks, I like talking about this philosophy. Sometimes I feel I bore people to death with it.

GR: No, it’s resulted in some good games, so it’s very interesting stuff.

P: Well, there’s more to come, more thrilling experiences, so just wait and see!

Frostpunk is out now for Xbox One, PS4, and PC. On the Edge is set to release this summer.