Offensive games are touchy subjects, and the concept of "offense" itself is a tricky, fluid thing. What offends one person doesn't offend another, and occasionally offense can be used as a tool for social change—that's the entire premise of satire, after all.

The issue is that "satire" has become something of a buzzword for "free from criticism." Offensive games certainly can have a purpose if they use satire to critique a common ideology or practice, but the problem is that "offense" and "satire" don't go hand in hand. Offense for offense's sake reeks of little kids swearing at school because they know they're not supposed to—it's not productive, and while it might be cathartic it does little to further any kind of meaningful conversation.

Further, satire is supposed to be witty—an important note that many offensive games fail to hit. It's not enough to provide an example of hypocrisy or offensive content and call it satire; the satire is in the critique, not in the content itself.

Drawing the line between satirical games and outright offensive games can be difficult. One person's satire is another person's offensive material, and of course, eliminating anything that might be construed as offensive isn't the right move. But sometimes, there are games that make that line feel extra distinct and clear.

Hatred: Cultural Critique or Outright Offensive?

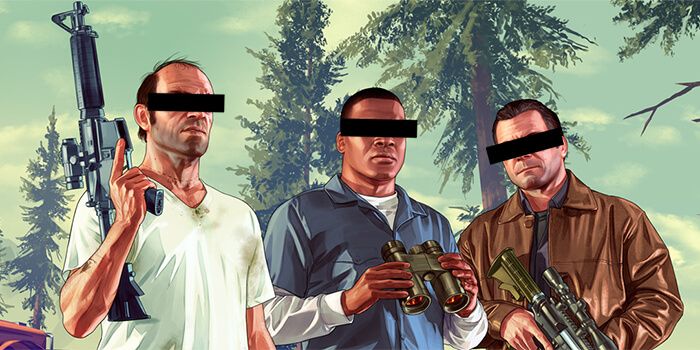

Hatred has drawn a lot of criticism for being highly offensive. It's an indulgent, ultraviolent game, and its priority is not story or character but pure, unadulterated violence. The game's raison d'être is not akin to Grand Theft Auto's humor and occasional social satire; it's violence for violence's sake, and the developers point out that there is "no compassion, no mercy, no point in going back."

That appeals to some people, and the game likely exists because there's a market for it. Some people have questioned why it's necessary to have a game like Hatred, as it's the type of game that those outside of the gaming community like to hold up as an example of the medium's overall problems—representing violence for violence's sake and having no higher aspirations. If that's the case, that's Hatred's problem; the firestorm surrounding the game has cemented that it's going to sell, and despite any uncomfortable feelings we might have about the way violence isn't constructed as a necessary evil in the game, the game is live.

There's a lot to critique in the way we think about violence in games, whether it's constructing violence as a means to an end in games like Uncharted, or as a painful yet necessary evil like in This War of Mine. You could claim that Hatred is making a statement in the way it revels in violence. Are the actions of a protagonist who guns down enemies (Nathan Drake, for instance) excused just because he's the good guy? How is Hatred different than approaching Grand Theft Auto as a sandbox murder simulator? Why is one game deplorable when the other isn't?

Unfortunately, it doesn't look like Hatred is trying to ask these questions. The game's website makes it pretty clear that it's purely about rejecting the notion that games should be "politically correct" and artistic. Instead, the sole intent was to make something extremely violent that would anger people—that's part of the reason many people are against it. Games like Grand Theft Auto approach satire in other ways—celebrity-obsessed media, our culture of excess, et cetera—but Hatred is a surface-level game that shows you violence and nothing else.

Offensive games like this incite a conversation. While that conversation might not be a civil one, it's a conversation nonetheless. Whether offensive games like Hatred are the best instigators for these talks is another debate, but, at the very least, Hatred's misanthropy isn't targeted; nobody is safe in the game's nihilistic world.

The Dangers of Offense for Offense's Sake

There are tons of games out there that intend to offend without any larger purpose. Games that mock people, games that consist of nothing but toilet humor, games that are gross in more ways that one. Many of these games stay in their own respective areas—posted on Newgrounds or on the developers' websites—because producing them for other platforms can lead to their rejection.

But that wasn't the case with a game called Kill the F****t (censorship added), which was admitted to Steam Greenlight and subsequently removed after complaints from users. Steam was within its rights to remove it, as the game violated their terms of service on offensive material and discrimination. And Kill the F****t doesn't fall under protected free speech because the game was rejected by Steam, a private entity, not the US government. You can't punch people in the face and handwave it away by saying you were only doing it to see their reaction. While there is obviously a difference between simulated violence and actual violence, the disproportionately high murder rate for LGBTQH individuals and the still-active climate of homophobia in our social and political system means we really do have to take things like this seriously.

What differentiates offensive games like this—games that are meant to incite nothing but anger—from games like Grand Theft Auto is that there is effort on the part of Grand Theft Auto developers to make a fun, engaging game in spite of the content that may be offensive. In games like Kill the F****t, anger and hate is the endgame, anger that's meant to draw in more players through pure controversy.

It might work, if the game didn't look about as appealing as one of those 'shoot the duck' advertisements from MySpace circa 2007. While nobody can stop these offensive games from existing—the Westboro Baptist Church prevails, despite the hate speech it continues to put out—we have to ask ourselves what the purpose is. Games that depend upon inciting anger to get attention are a little like kids throwing a temper tantrum in the grocery store. Except for the added aspects of extreme violence, which make them something worthy of concern and objection and more than just a nuisance.

"Satire" is not showing violence because you want people to get angry, and then laugh when they do. The sooner we can move past offensive games as a method of riling people up for publicity, the sooner satire will feel like a word with meaning again and not just an adult version of kids insulting one another and following it up with "just kidding."

Satire is a powerful tool for social critique, one that games can make great use of. But this isn't satire. There are shades of gray in the offensive games category, and it's not that we need to ban everything that might conceivably offend someone, but rather that, as a community, we should be conscious of the messages we condone and support.