As art forms mature, they journey into deeper and darker places. Just as popular literature grew to include indulgent penny dreadfuls and exploratory works on the human condition, many video games are taking the plunge into the often murky world of morality. Gamers no longer always play the lawful hero—series like BioShock and Mass Effect star flawed, complex characters who are constantly making difficult or damning choices that affect the outcome of the story. While BioShock's decisions are straightforward and minimal but extreme, Mass Effect's numerous small and complex decisions can change moments throughout the story. But which method has a stronger impact on gamers?

BioShock's Little Sisters present a clear-cut dilemma

2K Games' BioShock attracted attention for its original story and intensive world-building—Rapture is one of the most developed settings in any video game, instantly recognizable for its Art Deco aesthetics and decrepit atmosphere. A crucial part of the story centers on the Little Sisters—orphaned girls whose stomachs play host to a sea slug that produces ADAM, a very valuable material. Gamers take on the role of Jack, who uses ADAM-powered “plasmids” to defeat enemies.

As the players progresses in the game, Jack is influenced and guided by two sources, Atlas and Tenenbaum, who contact him separately over the radio with very conflicting instructions. Atlas urges Jack to kill the Little Sisters and harvest the ADAM for himself. Tenenbaum tells Jack to save the Little Sisters by injecting them with a plasmid to destroy the sea slug, and turn them back into normal girls. Killing them earns the player an immediate reward, while saving them nets the player special plasmids and the happiest possible ending.

The moral dilemma here is pretty straightforward and simple: killing innocent children is wrong, but doing so gains the player immediate resources and a survival advantage. However, thanks to unlimited respawns, gathering as much ADAM as possible isn't the only path to success. A player who chooses to save the Little Sisters might struggle a bit more at first, but is still fully capable of winning. BioShock's moral decision might feel extreme, but it only affects the player's immediate power and slightly alters the ending style—in ways that are predictable from the start.

Needless to say, BioShock’s Little Sisters dilemma doesn't have a very strong impact on players, whether they’re mainly concerned with power or story. For the former, the impact of a sad ending and the reprehensibility of eliminating Little Sisters doesn't upset the goal of gaining as much power as possible. For the latter, their savior struggles don’t significantly derail the ability to play and win.

Mass Effect's color-coded ethics take a more complex route

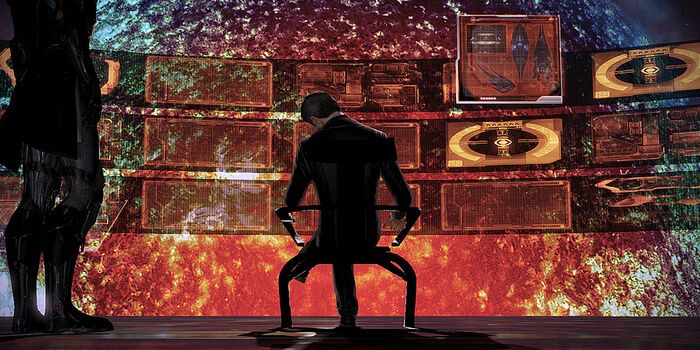

Mass Effect, BioWare's highly successful space opera, uses a different moral approach. As the galaxy-saving Commander Shepard, players can take multiple routes to achieve their ends: sometimes nice, sometimes ruthless, and sometimes in between. The two main paths—Paragon, which emphasizes diplomacy and tolerance, and Renegade, which relies on shooting first, asking questions later—are less black-and-white than BioShock's. Player choices have far-reaching consequences, too. As the player advances through all three Mass Effect games, past choices impact the story later on, with the notable exception of the game’s ending. Characters—including Shepard—can die, and decisions can mean sacrificing entire fleets to add to the war effort.

What’s most interesting about Mass Effect's system is that diplomacy-versus-ruthlessness doesn’t fully translate to good-versus-evil. The color-coding of the systems, blue for Paragon and red for Renegade, does create a dichotomy, but the series' infamous ending (SPOILERS to follow) challenges the idea of which path is good and which is bad, or whether any path can be labeled that easily.

And then there's the ending. It comes down to four choices: follow the blue path, follow the red path, choose to synthesize all life in the universe, or refuse to choose. By following the blue path, in which Shepard seizes control of the Reapers, Shepard dies but saves the universe. Refusing to choose results in the destruction of all organic life. By following the red path, Shepard destroys the Reapers but also the sentient, synthetic Geth—this is the only ending in which Shepard can survive. Synthesize, the third option, is only available if the player has gathered enough resources. In this scenario, Shepard combines his or her consciousness with the Reapers to change all life forms to synthetic/organic hybrids.

Mass Effect’s choices impact players’ ultimate survival, the livelihood of entire races of organisms, the state of the game universe itself, and players’ experience in the next series installment. This adds more weight to Mass Effect’s moral decisions, and requires players to balance the complex pros and cons of these different game outcomes. Compared to BioShock, the moral dilemmas of Mass Effect pack a far greater punch.

Muddying the moral game waters

Both BioShock and Mass Effect feature compelling moral dilemmas, but they are explored and realized to much different extents. BioShock’s Little Sister problem is a weighing of resources versus ethics, and constitutes a simple right or wrong decision for players that only slightly affects game experience. There are many interesting morality conversations to be had about the world of BioShock—such as how a world influenced by Ayn Rand’s concept of Objectivism functions, or about the overt sexual symbolism of the ADAM-producing sea slugs in the Little Sisters—but the central dilemma feels pretty black-and-white and low-stakes for players. Moral absolutes can be useful storytelling devices, but in comparison to the game’s inventive world-building and gameplay mechanics, BioShock’s moral system feels a little hollow and underdeveloped.

Mass Effect’s complicated system feels more like a true moral game. Paragon and Renegade are loaded terms, and the color-coded choices emphasize the dichotomy too neatly, but not all of the Paragon path’s choices have positive consequences and vice-versa. Overall, it’s difficult to say whether any ending is truly “good” when two out of three end in Shepard’s death, one involves changing the nature of all beings in the universe without their consent, and two eliminate entire races. This muddying of the divide between good and evil is a step in the right direction for asking effective moral questions in games.

By no means are these the only two examples of moral games—many current games feature dramatic choices that affect the ending, but these two in particular are recognized for storytelling depth and have received both praise and criticism for their unique exploration of moral themes. As the medium matures, so will its portrayal of moral issues. Newer indie games like Papers, Please, and Telltale's The Walking Dead are already exploring more complex moral issues without making one decision or another the "correct" one. While it's not the duty or obligation of video games to explore morality, it's a path many art forms follow, and games have a promising future for tackling this compelling subject.